Larks and Owls – Why Waking Early May Not Be Best For You

Early risers are praised for their effort and hard work. But science has shown that night owls may be even more productive, as long as they follow their body’s natural schedule.

What do you think of when you hear the word stress? While engineers may think of the load placed upon a bridge deck, psychologists may define it as an emotional response to a perceived threat that exceeds our ability to deal with it.

Today, however, we’re diving into a different kind of stress, the physiological kind. No, we’re not talking about the stress of realizing you left your coffee at home. We’re talking about the body’s response to external factors that disrupt your balance and leave you feeling anxious and agitated.

Stress can take a toll on us physically and emotionally, such as jumping into cold water or dealing with a family bereavement. But stress is not a new phenomenon; past societies had to deal with the stresses of hunting, famine, cold, and other environmental factors that our modern societies have thankfully moved past.

This article will overview the different types of stresses and provide practical tools and exercises that help you function effectively alongside them. The aim is to give you a greater awareness and control of your body and mind when stress inevitably rears its ugly head.

So, let’s take a closer look at stress, its different types, and some strategies to deal with it. Don’t worry; we won’t stress you out too much.

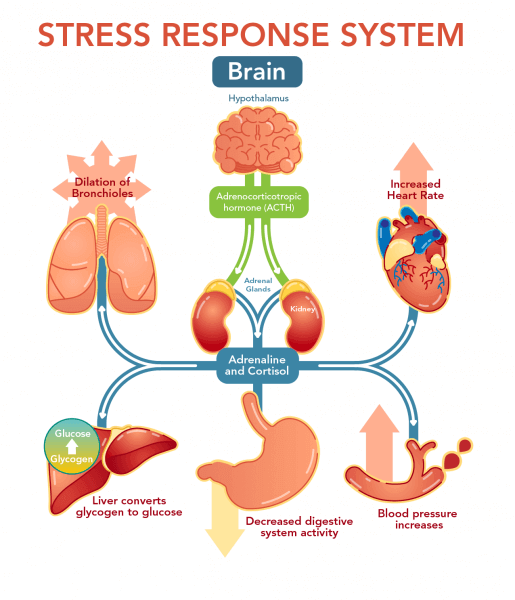

Stress has many different meanings depending on the use. What we are focusing on for this article, however, is the physiological meaning, the body’s response to any physical, emotional, or environmental factor that disrupts the body’s homeostasis (balance).

We often see stress manifest as tension and pressure that negatively affects us physically and emotionally, such as the rising cost of living making it more difficult to pay rent and take care of family.

It is true that current affairs, such as a tightening economy and political polarization, have introduced sources of stress that were not present just a decade ago.

Despite a rise in attention and awareness, stress is nothing new; for as long as humans have been capable of conscious thought, they have had to deal with stress.

Many believe stress to be a carryover from historical times, such as encountering dangerous animals or other tribes or humans. When a person went out to hunt, it was not certain that they would return, resulting in stress not just for the hunter, but also for the rest of their tribe.

There was also the stress of cold, famine, illnesses, and other environmental factors that do not now afflict our modern societies.

Stress can be caused by any stressor that induces the stress response, a mechanical response hard-wired into our nervous system and DNA. The types of stressors and the degree to which they induce stress are highly variable and depend on an individual’s nature and nurture.

For some, the very thought of giving a wedding speech will induce fear for months, while others might look forward to it. Some can deal with living each day in the moment, whereas others freak out if each minute isn’t planned and accounted for.

While acute stressors such as jumping into cold water, performing a 100-meter sprint, or banging your head on the corner of a cabinet may not seem to elicit much of a benefit, short-term stressors such as these have been shown to boost numerous advantageous processes in the brain and body.

The acute stress response has been shown to boost the immune system. Many of our short-term stressors are bacterial or viral (colds and flu), and our natural stress response organizes to combat these threats of infection.

The stress response also releases acetylcholine, a neuromodulator responsible for activating muscles (such as running from a potential threat), and releasing adrenaline, a hormone responsible for quickening your heart rate and sharpening your cognition and focus, both useful traits for dealing quickly with potential threats.

Many stressors, such as cutting yourself or banging your knee, will elicit a rapid inflammation response. We often hear that inflammation is bad, and in some situations it is, but inflammation is associated with the recruitment of things such as macrophages and microglia; cells in our brain and body whose job it is to rush to that site and clean it up.

So if you’re under short-term stress a few times a week, your brain and body will be in a better position to combat and fight against illness and infection. If you wish to control your stress, therefore, you need to learn how to work with it, because short-term stresses often provide invaluable benefits for both the body and brain that we cannot live without.

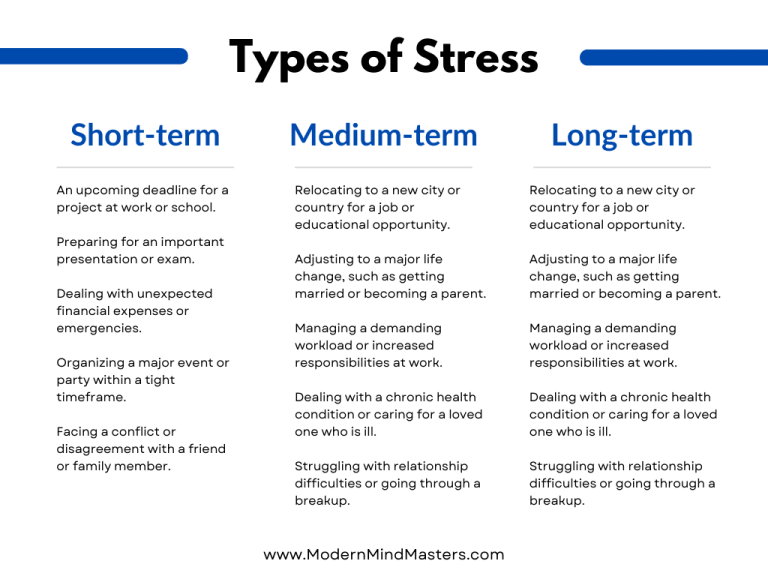

As a rule of thumb, whenever stress stops you from achieving a solid night’s sleep it can be considered medium-duration stress, lasting anywhere between several days and several weeks.

Whereas short-term stress tends to dissipate as soon as the stressor disappears, medium term-stress is not so easy to eliminate, meaning we need to learn how to deal with it.

Stress on the scale of months or years can be considered long-term. Having adrenaline and other stress hormones in your system for such long periods is hugely detrimental and will lead to serious physical and mental health issues.

This study showed a strong correlation between depression and anxiety and adverse Cardiovascular disease (CVD) events, suggesting that the metabolic activity of the amygdala, a neural center involved in the stress response, can be measured using neuroimaging techniques and independently predicts subsequent CVD events.

Another study came to a similar conclusion after analyzing over 150,000 patients in Sweden who received their first diagnosis of a stress-related disorder (such as acute stress reaction, post-traumatic stress disorder, or adjustment disorder) during a 26-year period.

The results showed that individuals with stress-related disorders had an elevated incidence of cardiovascular diseases, with the hazard ratios for the risk of cardiovascular disease 1.64 for less than one year and 1.29 for one year or longer after the diagnosis (a hazard ratio greater than 1 suggests that the event is more likely to occur in the group being compared to the reference group).

Knowing the different kinds of stresses (short, medium, and long-term), we can now implement practical exercises and tools to deal with each of them.

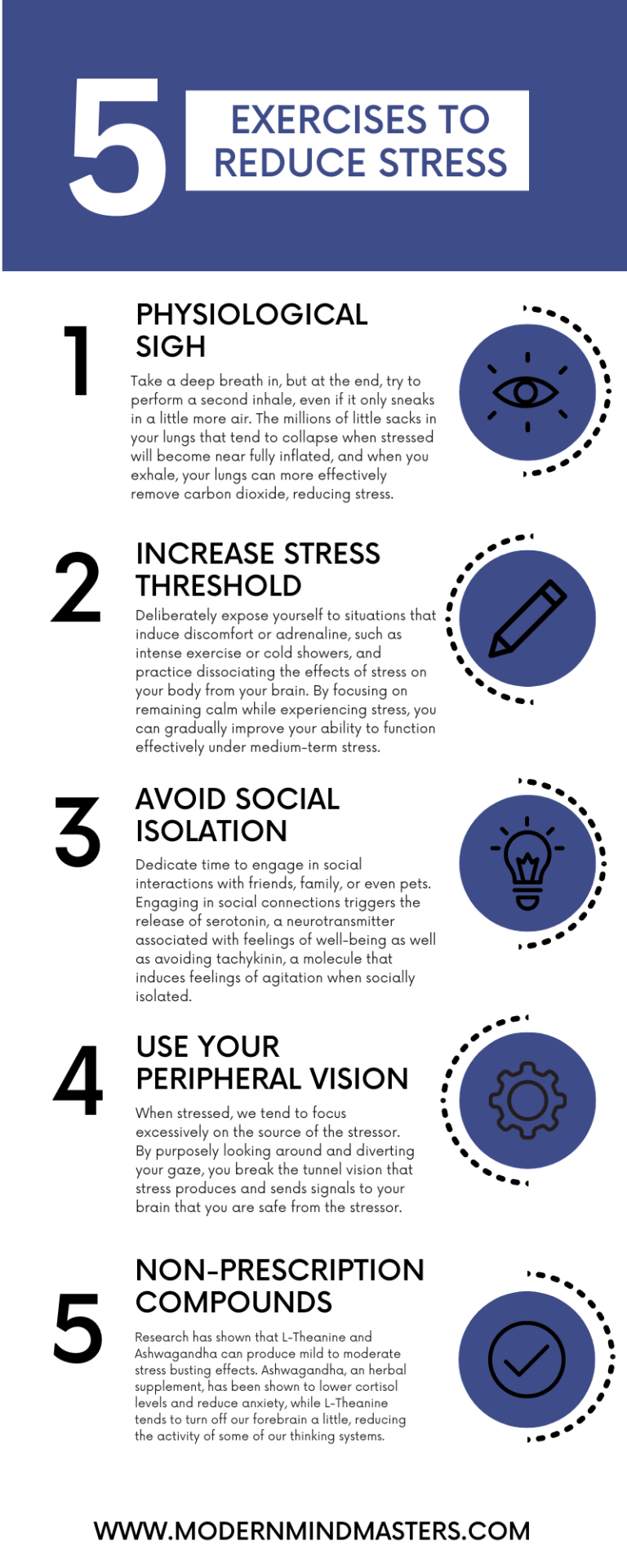

While sounding peculiar, the psychological sigh is something you frequently perform naturally without even realizing it.

The physiological sigh, also known as the sigh reflex or the deep breath, is characterized by a deep inhalation followed by a prolonged exhalation. We sometimes do it when we sleep, where too much carbon dioxide builds up in the lungs. It is also noticeable after crying when you breathe deeply to recover some air and calm down.

When inhaling a large breath of air, all of the millions of little sacks in your lungs (alveoli) fully expand, maintaining the elasticity and health of the lungs, promoting optimal gas exchange and preventing the buildup of carbon dioxide in the lungs (one of the reasons why we feel agitated when stressed). This dual action process helps to maintain a proper balance of gasses in the bloodstream.

One variant of the physiological sigh you can intentionally perform is the “double inhale”, where you take a large breath in, but just as you reach the top of your inhale, you take a second breath, even if it is small and only sneaks in a little more air.

After your second inhale, a slow exhale will now be much more effective at ridding your bloodstream and body of carbon dioxide. As a result, you can enter a state of greater relaxation rapidly.

Just three repetitions are enough to reduce your stress level quickly and in real time, but it can be performed as many times as it takes (as long as you feel comfortable) to start reducing your stress levels.

The physiological sigh is an excellent tool to eliminate stress using the same mechanical hard-wired mechanism that caused it. Top-down mechanisms such as mindfulness and gratitude, while they have their place, are not effective when the mind is in a heightened state of agitation, such as frustration or panic.

While breathing techniques such as the physiological sigh are excellent tools for short-term stressors, stress spanning longer periods requires different tools.

Since stress is an inherent and automatic process (the stress response is hard-wired and does not involve neural plasticity or cognitive ability), there is no way to avoid it; instead, we must learn to operate effectively alongside it.

We can do this by increasing our stress threshold, the point at which our ability to cope with stressors or demands exceeds our capacity to effectively manage them. It represents the point at which stress begins to have a significant negative impact on our well-being, mental health, and overall functioning.

You can learn to increase your stress threshold by deliberately placing yourself in situations where you are exposed to elevated levels of adrenaline.

Cold showers are an extreme example. Try standing under a cold shower and you are unlikely to last even a few seconds. But slowly increasing your exposure to cold showers will, over time, make it feel more manageable as you build your tolerance to it.

Exercise such as high-intensity cardio is another excellent way to practice increasing your stress threshold. When exhausted, and your body and brain begin to fatigue, practice focusing on mentally and emotionally calming yourself, while being mindful and in control of the stress response taking place in your body.

What you are practicing here is dissociating your body and mind in a healthy way to teach the mind to relax while the body is highly activated and under stress.

With practice, what once felt overwhelming, such as a 10-second cold shower or a five-minute run, will start to feel manageable. Thus, you’ve raised your stress threshold, and your ability to cope with stress will transfer across all aspects of your life.

When stressed, we tend to narrow our vision, both literally and figuratively, to focus our senses and resources on the stress at hand.

The result is “tunnel vision” on the stressor, such as how we immediately forget a person’s name when meeting someone because we are focused on the stress of what the other person is thinking of us.

Since stress is a two-way mechanism, where stress causes us to narrow our focus, we can manually widen our focus to reverse the response. Whereas a stressed mind sharpens on the stressor, a wider gaze infers to the brain through the stress response that it is safe and that the stressor is no longer present.

When stressed, deliberately dilate your gaze and focus on your peripheral vision. Look at the wider environment and pay conscious attention to the things around you. You will notice a calming effect on the mind because it releases a particular circuit in the brainstem that is associated with alertness and stress.

When exercising, for example, and your body is highly activated, consciously focus on your surroundings (within reason, of course, don’t be looking at the ceiling while running on the treadmill). Over time, you will begin to feel more comfortable in these high activation states, and what once felt overwhelming and a lot of work will now feel manageable.

No self-improvement article regarding mental and physical self-improvement is complete without the usual three vital aspects of health, the Holy Trinity of nutrition, exercise, and sleep. When just one of these components is missing, the effect is so significant that all other tips here become near irrelevant.

See this article for how to improve your exercise – The 7 secret benefits of Exercise.

See this article for how to improve your sleep – The ultimate guide to falling (and staying) asleep.

While deep breathing techniques and increasing your stress threshold can help alleviate short and medium-term stressors, the question remains how we can deal with long-term stress?

We know that regular sleep, exercise, and maintaining a healthy diet are fundamental for long-term health, but data has shown that avoiding social isolation through regular social connection can improve long-term stress considerably.

Humans are social creatures by nature; human prosperity has typically relied on the strength of the tribe, and depriving ourselves of our social needs releases chemicals in the body that signal we are in danger of social isolation and will lead to long-term stress.

One of the key chemicals involved in long-term stress is serotonin, a neuromodulator that gives us feelings of well-being and a sense of content, two reasons why they make for effective antidepressants (albeit with some side effects).

Studies have shown that serotonin is released in the brain when we see someone we know and trust, resulting in several positive effects, such as strengthening the immune system, increased neural repair, and a sense of well-being.

When deprived of social connections, however, not only are we deprived of serotonin, another hormone called tachykinin is released, which makes us feel fearful and paranoid.

This may seem counterintuitive; why would the body release a harmful compound when we are already socially isolated?

But the brain is one step ahead of us. When socially isolated, it releases tachykinin, a neuromodulator that signals to your brain that you are not spending enough time with people that you trust, which, at a primitive level, is a way of your body telling you that you’re away from the safety of your troop, and you must act to return to it.

The types of social connections that will increase serotonin release while inhibiting tachykinin can take many forms, but common examples are long meals with friends, gatherings with family, and even an attachment to pets has been shown to boost social engagement.

Social connection is often one of the first activities that suffer when stressed; between worsening financial conditions and trying to balance a career and family, dedicating time to social events often slips down the priority list.

But it is something that we have to work hard for and be flexible with – it requires sacrifice in terms of time and schedule.

There are a few effective non-prescription compounds that have been shown to have a stress-reducing effect on the brain. These are not antidepressants (only a doctor or qualified professional can assist in whether that may or may not be right for you), but rather natural compounds that can modulate the stress response, perhaps taking the edge off some of your more stressful moments.

Melatonin, a hormone secreted from the pineal, is responsible for helping you fall asleep in relation to natural light levels around you. As night draws and it gets darker, melatonin levels increase to prepare you for sleep.

But melatonin has also been shown to modulate the release of cortisol, a stress hormone that is typically higher in the morning to help wake you up, which gradually decreases throughout the day. By influencing this cortisol rhythm, melatonin can potentially reduce excessive cortisol levels that contribute to chronic stress.

For many, however, melatonin supplements are not advised because the supplements you buy are typically at very high levels of around 1-3mg, way above typical natural peak levels which range from 10 to 100 picograms per milliliter (pg/mL). It has also been shown to have negative effects on hormones and the reproductive system.

While it may help some people in the short term, those who take melatonin supplements chronically can find that the benefits of stress and anxiety reduction are offset by more problematic side effects.

L-theanine is an amino acid primarily found in tea leaves, especially green tea, and is commonly used as a dietary supplement for its potential stress-reducing and relaxation-promoting effects.

Whether taken in a supplement form or naturally from green and matcha teas, L-theanine has been shown to turn off the active regions of our forebrain by increasing the inhibitory neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), allowing us to enter an increased state of relaxation.

While commonly used for sleep, multiple studies have shown minor but noticeable effects on reducing stress and anxiety. It can also reduce task completion anxiety, one reason why many companies are now putting theanine into energy drinks.

While ashwagandha may sound like the name of a spell from a Harry Potter film, its name is derived from the Sanskrit words “ashva,” meaning horse, and “gandha,” meaning smell, because the roots of the Ashwagandha plant have a strong, distinct odor similar to that of a horse.

Available in various forms, including capsules, powders, extracts, and teas, ashwagandha has been shown across many studies to reduce cortisol, a stress hormone, by 15-30% in otherwise healthy but stressed adults.

You should never rely on any supplement to reduce your stress, but when taken in times when you feel you are not able to sufficiently deal with your medium and long-term stress by yourself, research has shown that they can help take the edge off.

Stress is a natural and inevitable part of our lives, and so long as we have dreams, goals, and aspirations, stress will be an inevitable occurrence.

In the short term, the stress response provides numerous benefits, from boosting our immune system to helping focus and quicken the body and brain to deal with stressors and potential threats.

When stress begins to affect our sleep and lasts for multiple days, however, it often proves detrimental and can be deemed to be of a medium or long-term nature.

Because the stress response is a hard-wired mechanical reaction, there are some simple exercises we can do to manually reverse it.

For short-term stress, try utilizing your breathing to signal to your brain that the stress is manageable. Performing the physiological sigh, by taking a second breath to squeeze in extra air after already having inhaled fully, and then slowly exhaling, is an excellent way to reduce stress and anxiety rapidly and in real time. Diverting your gaze when stressed is also an excellent way to reduce the effects of short-term stress.

For medium and longer-term stress, however, we need to be proactive by increasing our stress threshold by practicing separating the stress between the body and brain. Ensuring you avoid social isolation is also essential to avoid the release of tachykinin, which has been shown to induce feelings of fear and paranoia.

In the end, stress is an inevitable part of life, but armed with these science-backed exercises, you can navigate the deepest of waters with a greater sense of calm and control. So take a deep breath, widen your gaze, embrace a healthy lifestyle, nurture your relationships, and remember, stress may knock on your door, but you don’t have to invite it in for tea.

Early risers are praised for their effort and hard work. But science has shown that night owls may be even more productive, as long as they follow their body’s natural schedule.

Mindfulness, the state of being aware of something, is the fundamental trait of awareness and self-improvement. Learn how to master this lost art.

Success stems from many small wins compounded over time – the key to this is consistency, which is achieved though the use of strong habits.

Do you really need fiber, or is this simply an overhyped myth? Science and anecdotal evidence now suggest the body can run better without it when on a low-carbohydrate diet.

Emotions stem from the limbic system, an impulsive and primal part of the brain that is extremely powerful. Unfortunately, no one teaches us how to manage emotions, but thankfully these books will.

Habits are the foundation of success and we are merely the result of good habits compounded over time. Here are the best 3 books on habits that will change your life.

© 2025 Modern Mind Masters - All Rights Reserved

You’ll Learn:

Effective Immediately: 5 Powerful Changes Now, To Improve Your Life Tomorrow.

Click the purple button and we’ll email you your free copy.