Is ADHD Behind Analysis Paralysis?

Analysis paralysis occurs when overanalyzing a situation results in a lack of ability to make a decision. These effects are worsened in those with ADHD, leading to ADHD paralysis.

Whether a demanding job, young children to take care of, or how you’re going to pay next month’s rent, we all have our fair share of stress to contend with.

Long-term stress is a literal killer; according to the American Psychological Association (APA), chronic stress is linked to the six leading causes of death: heart disease, cancer, lung ailments, accidents, cirrhosis of the liver, and suicide.

Long-term stress is a literal killer; according to the American Psychological Association (APA), chronic stress is linked to the six leading causes of death: heart disease, cancer, lung ailments, accidents, cirrhosis of the liver, and suicide.

But not all stress is bad; in fact, we have relied on our stress response to overcome the natural dangers of life and emerge as the dominant species. The key is to identify the type of stress affecting you and develop tools that ensure you can function productively alongside it.

This article will provide valuable science-based insights and practical exercises to help you navigate stress more effectively. By embracing stress as a natural part of life and learning to work with it, you can enhance your well-being and build resilience to face life’s challenges.

Stress means many things to different people, but most fundamentally, it refers to experiencing too much of something.

In biology, this could be experiencing too much hunger or cold. Psychologically, it could occur when suffering from an overwhelming workload at your job. In engineering, something is stressed when placed under a load, such as the span of a bridge.

We experience stress when exposed to a stressor, an internal experience or event that causes stress to an organism. Stressors can be anything, from the physical cold from a cold shower to the fear of presenting in front of your peers.

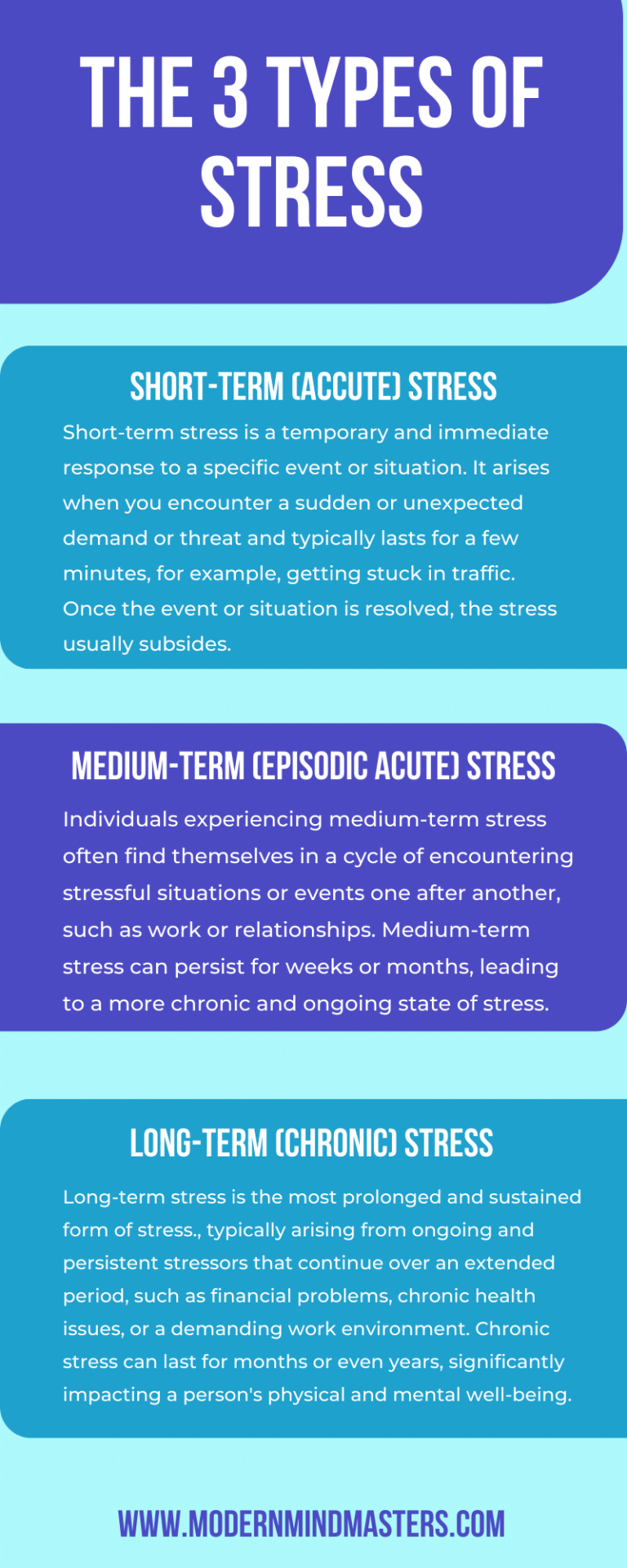

We often think of stress as long-term constant pressure, such as dealing with the illness of a loved one or trying to overcome debt problems.

But most types of stress are acute, that is, short-term. Getting frustrated with a careless driver on your commute, walking to your car when it’s icy cold, or stubbing your toe when navigating around all your child’s toys left on the floor are all acute stressors that activate the body’s stress mechanisms.

These acute types of stressors are easily overcome and typically last only as long as the stressor is present. Once the pain subsides or the arrogant driver disappears, the stress dissipates with it.

As a general rule of thumb, a stressor that prevents you from falling asleep quickly and obtaining a good night’s sleep can be thought of as medium-term. Worrying about a work task tomorrow or exams next week often affects our ability to sleep and is therefore considered medium-term stress.

Medium-term stress can last anywhere from a few days to a few weeks. Anything beyond this would be considered longer-term stress. Importantly, the tools for dealing with short, medium, and long-term stress are different, as we will soon learn.

Before we can learn to deal with stress, it is imperative we first understand the mechanics behind it.

For as long as humans have been able to think, they have had to deal with the weight of stress. Many believe it to be a carryover from more primal times, where there was no limit to the number of stressors, including potential famine, cold, disease, predators, and other humans.

Since stress often results in fear, anxiety, and many other detriments, why have a mechanism for it at all? And in modern societies where many of these stressors are no longer present, should we seek to ignore and overtime this burden?

Fortunately, the body and brain are more clever than we think. Stress is an essential mechanism to help us overcome the risks and potential perils that saturate our daily lives.

For some, stress is clear, such as a new parent trying to learn the ropes while sleeping very little. For others, it is much more subtle; some live with stress so long that they may not even realize they are suffering from it.

Stress and anxiety can trigger physiological and psychological responses in the body, which commonly manifest as chest pain or discomfort.

Stress increases acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter that activates muscles. An increase in stress increases muscle tension throughout the body, including the chest, leading to discomfort or pain.

Acetylcholine increases the production of another hormone, epinephrine (also called adrenaline), responsible for activating the “fight or flight” response in the body, increasing heart rate and blood pressure, which may result in a pounding or pain in the chest.

In more severe cases, stress can cause hyperventilation, where a person breathes rapidly and shallowly, disrupting the balance of oxygen and carbon dioxide, leading to symptoms such as chest pain and tightness.

A more curious symptom of stress reported by many is feeling itchy when stressed – what is known as stress-induced pruritus. Although the exact mechanisms behind it are not fully understood, there are some plausible theories.

Firstly, stress can heighten sensitivity to various senses, including itchiness, which may amplify the perception of itch signals in the brain and lead to a heightened itch sensation.

Secondly, the reason could be more physiological, such as stress contributing to changes in the skin’s barrier function, leading to increased water loss and dryness – two changes we know make skin more prone to itchiness and irritation.

A third reason could be neurological, such as stress triggering the release of stress hormones, such as cortisol, which can activate certain nerve fibers involved in itch sensation, leading to increased itchiness.

While stress is a normal response to challenging or overwhelming situations, chronic or excessive levels can have negative effects on mental health.

Prolonged stress can disrupt the natural and delicate balance of stress hormones in the body and brain, such as dopamine, epinephrine, serotonin, and cortisol, all of which play a role in mood and emotion regulation. Imbalances in these chemicals can contribute to the development of anxiety and depression.

Nothing kills a healthy diet and weight loss effort faster than long periods of chronic stress. With so many other stressors to attend to, secondary matters such as diet and exercise routine are the first to go out the window.

When stressed, many turn to food as a way to cope with their emotions, leading to overeating, especially high-calorie comfort food such as ice cream and fast food. Referred to as stress eating, this bad habit will contribute to weight gain over time.

Elevated levels of stress hormones such as cortisol can affect metabolism, appetite regulation, and fat storage, leading to weight gain in some individuals.

Additionally, stress often disrupts our ability to obtain sleep of sufficient quality and quantity, an effect associated with weight gain and an increased risk of obesity.

While stress may seem inherently negative, your body and brain rely on it for some rather clever biology.

Various studies have shown that acute stress is good for your immune system. This study showed that acute stress, lasting for minutes, can mobilize certain immune cells and increase pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Since many stressors come in the form of bacterial or viral infections, it is clear that a stress response that mobilizes certain immune cells is extremely useful in combating threats of infection.

If you’re under short-term stress a few times a week, your brain and body will be better positioned to combat and fight against illness and infection. We can even use stress to help protect ourselves against common illnesses such as colds and flu.

Longer-term stress, however, was found to have the opposite effect. Chronic stress, lasting from days to years, is associated with higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and can lead to chronic systemic inflammation and activation of latent viruses.

Acute stressors activate specific neural pathways and parts of your brain that quicken heart rate and sharpen cognition, allowing you to focus on and deal with the stressor and hand.

For example, when walking down the street and you hear a loud bang, your heart rate increases, and you immediately attempt to focus on the source of the noise.

This makes sense when you think about more primitive stressors such as famine and predators, where a sharpening of the senses will help you focus on finding food or engaging your fight or flight response.

Have you noticed that you mostly procrastinate when not stressed by impending deadlines or final dates?

We procrastinate because our subconscious “chimp” craves instant gratification, and watching TV now while working later satisfies this urge. To force ourselves against this urge, we have to apply a significant amount of mental energy (willpower) to overcome this limbic friction.

When we procrastinate, we are sort of self-imposing stress. Stress is the most powerful “get it done now” drug known to man. As we continue to procrastinate and the incoming deadline looms closer and closer, our stress levels rise until the point where it overcomes our urge to procrastinate.

Unlike many other neural systems, such as learning and memory, stress does not involve the neuroplasticity of the brain, meaning you cannot use the power of thought to override or influence it. The stress response is a direct mechanical pathway hard-wired into the nervous system.

Stress, therefore, is a generalized system – it responds to many variables and does not differentiate between different types of stress. To your body and brain, the stress from an upcoming exam is the same as that from jumping into icy water. As a result, the same biological reaction occurs in both scenarios.

While not being able to override stress using thought alone may sound worrying, it is a double-edged sword. While thought does not allow us to overcome it, we can use simple mechanics, like breathing, to mitigate or even turn the stress off.

The stress response starts with a special group of neurons called the sympathetic chain ganglia – sympathetic coming from the Greek word “sym-patheia,” which means “feeling or suffering together”.

These neurons run along your spine between your neck to just below your navel, and when your body encounters a stressor, whether emotional or physical, this chain of neurons activates very quickly, releasing a neuromodulator called acetylcholine at various sites around the body.

In the brain, acetylcholine is used for focus. In the body, it is used whenever we move by connecting spinal neurons to muscles to induce movement.

The release of acetylcholine also releases other neurons, called postganglionic neurons, releasing adrenaline (epinephrine) which combines with acetylcholine to unleash an instant burst of power and performance.

The parts of your body that need to react to stressors, such as your legs (for running) and your heart (for increasing blood flow), contain beta-receptors – a receptor that causes blood vessels to dilate.

For your legs, expanding vessels increases blood flow into the muscles and boosts both power and endurance, useful for running away from potential threats and stressors.

As previously mentioned, stress is a generalized system and is therefore limited in its flexibility – it is either on or off.

When turned on, the activated epinephrine activates some receptors but also deactivates others in tissues and systems that we don’t need, such as those affecting digestion and reproduction that may be considered luxuries in acutely stressful situations. It does this by binding to receptors that contract the blood vessels, temporarily disabling them.

You can think of the stress response as an on/off switch, activating some parts of your body it deems necessary while disabling those it doesn’t. This is why many get a dry throat when stressed, as the salivary glands are temporarily switched off.

As you can see, acute stress plays a pivotal role in increasing our immune defenses, activating healing processes, increasing focus, and priming our bodies for performance in stressful situations.

As a result, the common belief that stress is a burdensome carryover from more primal times, and in our modern civilized and safer societies, it is something to be avoided and eliminated, is misguided.

Avoiding stress is neither possible nor desired. Instead of looking to avoid it, we should learn to operate alongside it, receiving the benefits it offers while minimizing its longer-term detriments.

While stress will always be a part of our lives, learning to function effectively alongside it will minimize its detrimental effects while maximizing your performance alongside it. Here are three exercises you can develop to help manage your stress.

The physiological sigh is something that humans and other animals perform naturally anytime they are about to fall asleep. You may also have noticed it after intense crying, where you breathe vigorously to calm down and recover some air.

It is often referred to as a “sigh of relief” and serves as a natural mechanism to help restore balance in the respiratory system. It can quickly decrease stress levels by rapidly ridding your bloodstream of carbon dioxide.

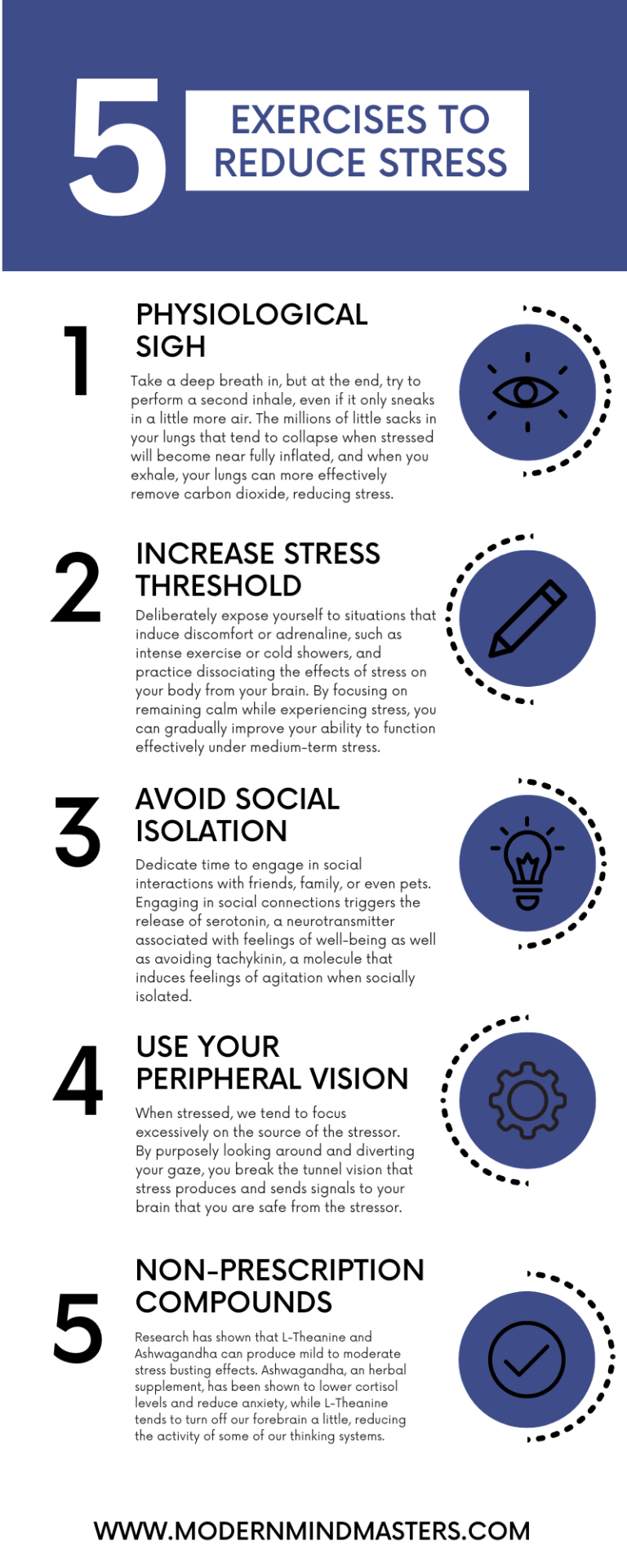

To do this exercise, take a deep breath in, but at the end, try to perform a second inhale, even if it only sneaks in a little more air. The millions of little sacks in your lungs that tend to collapse when stressed will become near fully inflated, and when you exhale, your lungs can more effectively remove carbon dioxide.

Performing even just three double inhales can be enough to start reducing your heart rate and stress levels, but it can be performed as many times as needed to reduce your stress quickly and in real-time.

While the physiological sigh is a good technique for reducing short-term acute stress, medium-term stress requires a different approach.

By its nature, medium-term stress cannot be eliminated through breathing exercises alone, so if we want to control it, we need to learn to work alongside the agitation that stress creates.

We do this by slowly increasing what is known as our “stress threshold”, that is, our ability to effectively work while under the effects of stress.

While a lot of new-age speak emphasizes the need for body and brain to become one and work together, we actually need to practice dissociating them. We need to separate the effect of stress on the body from the brain for one to keep performing while the other is struggling.

One way to practice this is to deliberately place yourself into situations where your adrenaline increases and you start to feel uncomfortable.

Exercise is an excellent way to achieve this. When reaching a point of fatigue while running, for example, practice focusing on cognitively, mentally, and emotionally calming yourself while attempting to become comfortable with the stress on your body.

Cold showers are another great (albeit uncomfortable) way to practice this mind-body stress dissociation. After a few days and weeks of practicing remaining calm under the discomfort of cold water, the amount of time you can spend under it will begin to increase, thus increasing your stress tolerance.

Assuming you have the holy trinity of health in order (sleep, diet, and exercise), increasing and improving the quality of time spent in social situations has been shown to reduce the long-term effects of stress.

Humans are, by nature, creatures of habit, and depriving ourselves of social connections, no matter how independent we like to think we are, can lead to prolonged stress. Social connection can take various forms, including relationships, friendships, and even enjoying the company of pets.

Social interactions trigger the release of serotonin, a neurotransmitter associated with feelings of well-being. When in social isolation, however, a molecule called tachykinin is released, which studies have shown has negative effects on mental and physical health.

Long meals with friends or spending time with family can help reduce stress by suppressing tachykinin, which is released when the body believes itself to be in social isolation.

Ensure you dedicate enough time each week to meet your basic social interaction needs. Dedicating time to do this with a career and family is no easy feat, and some flexibility and sacrifice will be needed, but your brain and body require it to mitigate the effects of long-term stress.

tress is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon that affects us all in different ways. But we all tend to suffer from similar symptoms, such as chest pain, itchiness, anxiety, depression, and weight change.

Stress can be categorized into short, medium, and long-term types, each requiring different coping strategies. While acute stressors are typically short-lived and easier to overcome, medium and long-term stressors can have more significant impacts on our mental and physical health and require more attention to manage.

It is vital to recognize that stress is not inherently negative. Acute stress has many benefits, such as boosting the immune system, increasing focus, and reducing procrastination. By understanding and harnessing these positive aspects, we can learn to work alongside stress rather than trying to eliminate it.

The stress response is a hard-wired mechanical process that works both ways in creating and reversing the effects of stress. Some techniques to counter this include the physiological sigh, increasing our stress threshold, and ensuring we avoid long periods of social isolation where molecules such as tachykinin develop an agitation within us.

Ultimately, stress is a natural and unavoidable part of life. Instead of trying to eliminate it completely, we should strive to develop resilience and coping mechanisms to navigate through it. So, instead of stressing about stress, let’s embrace it, manage it, and show it who’s really in control.

Analysis paralysis occurs when overanalyzing a situation results in a lack of ability to make a decision. These effects are worsened in those with ADHD, leading to ADHD paralysis.

Intermittent fasting, where we eat across a specific time frame only, unlocks an array of benefits, both psychical and physiological.

The benefits of grounding have been scientifically studied and include reductions in inflammation, diabetes, and stress.

Follow these 7 simple steps that work alongside your body to learn how to stop oversleeping.

While Intelligence is linked to success, it is genetic and cannot be significantly improved. Persistence, therefore, is what we must focus on.

Knowledge is not power without action, and habits form the consistent actions that compound over time to guarantee success.

© 2024 Modern Mind Masters - All Rights Reserved

You’ll Learn:

Effective Immediately: 5 Powerful Changes Now, To Improve Your Life Tomorrow.

Click the purple button and we’ll email you your free copy.