Key Points

- Modern evidence shows that omega-6 seed oils oxidize easily, promoting inflammation and metabolic dysfunction when consumed in excess.

- Large meta-analyses now confirm no clear link between saturated fat and heart disease, overturning decades of dietary advice.

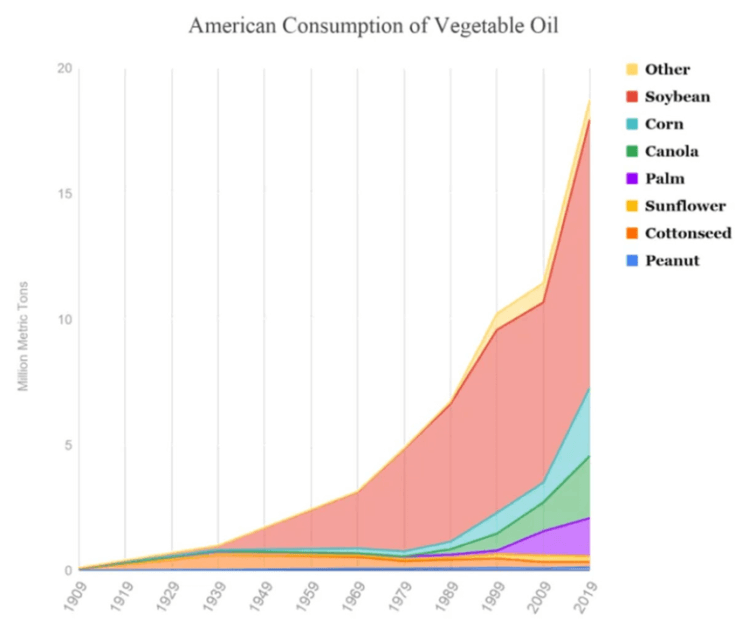

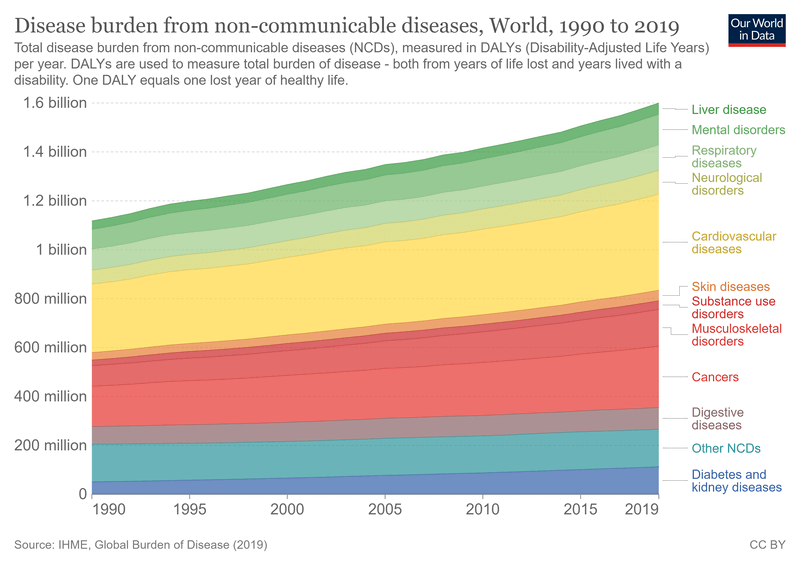

- Since 1900, seed oil consumption has risen over 1,000 percent, paralleling dramatic increases in obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Table of Contents

Few topics in nutrition are as divisive as seed oils.

To some, they’re a heart-healthy alternative to animal fats — endorsed by doctors, dietitians, and health organizations around the world. To others, they’re an industrial invention at the root of modern metabolic disease.

So which is it?

Are seed oils the unsung heroes of cardiovascular health — or the silent saboteurs behind inflammation, obesity, and chronic illness?

In this article, we’ll break down what seed oils actually are, how they became so dominant in our diets, what the science really says (on both sides of the table), and why a closer look at biology, history, and funding reveals a much more complicated truth.

What Exactly Are Seed Oils?

Seed oils, sometimes called “vegetable oils,” are industrially extracted oils derived from the seeds of plants such as soybeans, corn, sunflower, cottonseed, safflower, and canola (a cultivar of rapeseed).

Despite the friendly name, these oils have little in common with traditional fats like olive oil, butter, or tallow, which can be obtained through simple pressing or rendering. Producing seed oils requires heavy mechanical and chemical processing to release oil from the small, hard seeds that naturally contain very little of it.

The extraction process typically involves grinding the seeds, heating them to high temperatures, and washing the mash with a petroleum-based solvent such as hexane. The crude oil is then refined to remove impurities, bleached to strip color, and deodorized to eliminate the strong odor produced during processing.

The end product is a clear, odorless, and shelf-stable oil that can withstand long storage and shipping—an attractive property for large-scale food manufacturing.

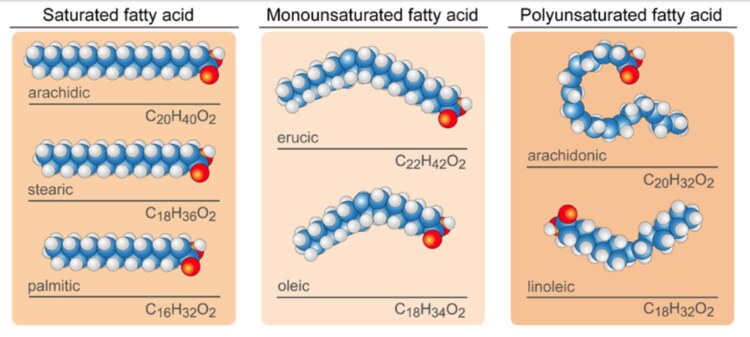

From a chemical standpoint, seed oils are dominated by polyunsaturated fatty acids, particularly linoleic acid, an omega-6 fat. These molecules contain multiple double bonds, which makes them flexible and fluid at room temperature but also more prone to oxidation when exposed to heat, light, or air.

This instability is why these oils can go rancid more easily than saturated or monounsaturated fats. In contrast, traditional fats such as butter, ghee, and tallow are rich in saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids that resist oxidation and remain stable during cooking.

A (Very) Brief History of Seed Oils

For most of human history, fats came from animals and from naturally fatty fruits such as olives, coconuts, and avocados. These sources required minimal processing — butter was churned, tallow was rendered, and olive oil was pressed. The idea of extracting edible oil from small, dry seeds would have seemed absurd to previous generations, simply because the yield was too low to be practical without modern machinery.

That changed in the late nineteenth century, when industrial refiners discovered ways to repurpose what was previously agricultural waste. Cottonseed, for example, had been an unwanted byproduct of the textile industry until engineers learned to press and chemically extract its oil.

The resulting product, after refining, bleaching, and deodorizing, was first sold for soap and lamp fuel. It wasn’t long before food manufacturers realized that with enough processing, the same oil could be marketed as a cheap substitute for butter or lard.

By the early 1900s, companies such as Procter & Gamble were producing hydrogenated cottonseed oil under the brand name Crisco. Its long shelf life and low cost quickly made it a staple in American kitchens, and it opened the door for similar products based on soy, corn, sunflower, and safflower oils.

The transition accelerated after the 1950s, when researchers began linking saturated animal fats with heart disease. Public health campaigns urged people to replace butter and tallow with “heart-healthy vegetable oils,” and the food industry was more than ready to meet the new demand.

Over the next few decades, global production of seed oils skyrocketed. In the United States alone, soybean oil consumption increased more than a thousand-fold between 1900 and the early 2000s, while traditional animal-fat use steadily declined. By the end of the twentieth century, seed oils had become the default fat in processed foods, restaurant fryers, and home pantries across much of the developed world.

This dramatic shift — from traditional, stable fats to industrially refined oils — represents one of the largest dietary experiments in human history. Understanding how and why it happened provides essential context for assessing their true impact on modern health.

The War on Saturated Fat

The story of seed oils cannot be told without revisiting the war on saturated fat. In the 1950s, a physiologist named Ancel Keys proposed the Diet–Heart Hypothesis, suggesting that saturated fat raised cholesterol and that cholesterol caused heart disease. His Seven Countries Study appeared to show a link between saturated fat intake and heart disease rates, but the data were selective — only the countries that supported his theory were included, while others like France, where people ate plenty of butter and cheese yet had low heart disease, were ignored.

Despite its flaws, Keys’ hypothesis shaped global nutrition policy for decades. Governments and health agencies urged people to cut back on saturated fat and cholesterol, while food companies rushed to fill the gap with low-fat products and “heart-healthy” vegetable oils. This shift marked the beginning of our modern dependence on seed oils — a change built not on strong evidence, but on a convenient narrative.

Biologically, the idea that saturated fat is harmful never made much sense. Human breast milk — arguably the most perfect food nature has designed — is roughly 50% saturated fat, yet we have no concerns about babies drinking breast milk. The body itself creates and stores energy as saturated fat, and uses it to build cell membranes, produce hormones, and insulate nerves. These fats are chemically stable, resistant to oxidation, and form the structural backbone of healthy human tissue.

Modern research has now largely vindicated saturated fats (from healthy unprocessed sources). Large meta-analyses published in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2010) and Annals of Internal Medicine (2014) found no significant link between saturated fat and heart disease. A 2020 review in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology went further, concluding that saturated fat intake shows no clear association with cardiovascular risk.

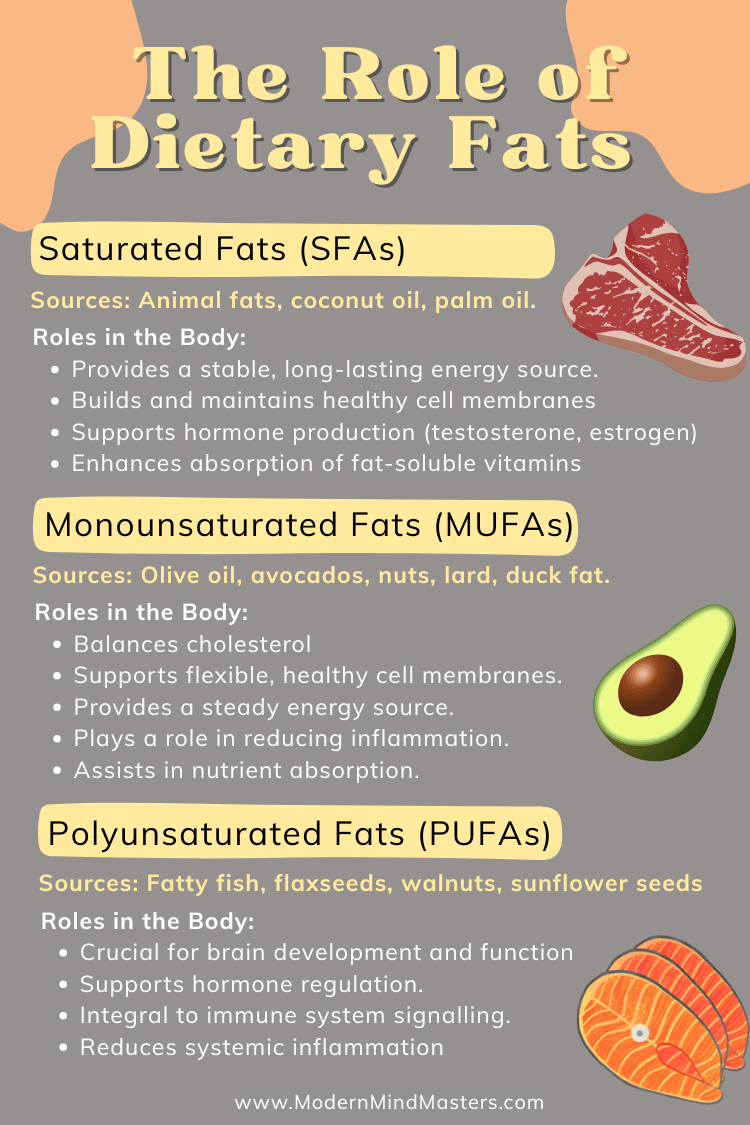

The emerging consensus is simple: balance matters. The body needs a mix of saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fats — but it has no need for trans fats.

When saturated fats were falsely labeled as dangerous, they were replaced with refined vegetable oils high in unstable omega-6 polyunsaturated fats. These oils oxidize easily, especially when heated, forming harmful by-products that promote inflammation and damage lipids in the bloodstream. In other words, the attempt to remove one so-called “bad fat” ushered in something far worse.

With today’s understanding of human biology, historical data, and the financial influence behind modern dietary advice, the science supporting seed oils looks increasingly shaky. The case against natural fats was built on weak evidence, while the evidence against industrial oils grows stronger every year.

For a deeper look at how saturated fat was wrongly blamed — and what the latest science actually says — see this article here: Is Saturated Fat Bad for You?

What the Literature Says: The Mixed Evidence

Reviewing the scientific literature on seed oils has been one of the most challenging parts of this topic. The data are messy, often contradictory, and heavily influenced by who funds or interprets the research.

On one side are studies that continue to frame saturated fat as harmful, arguing that replacing it with vegetable oils lowers cholesterol and reduces cardiovascular events. On the other are researchers pointing to a very different mechanism — that the high omega-6 content of seed oils promotes oxidation, inflammation, and metabolic dysfunction.

Both camps cite data, both claim to be backed by “strong evidence,” and yet they draw almost opposite conclusions. Untangling this web means looking past headlines and understanding how study design, biomarkers, and biochemical context all shape what we think we know about fat and heart health.

The Case For Seed Oils

Supporters of seed oils argue that these fats have played a crucial role in improving heart health over the past century. The reasoning is straightforward: polyunsaturated fats, especially omega-6 linoleic acid, lower total and LDL cholesterol when they replace saturated fat in the diet, and lower cholesterol is believed to reduce the risk of coronary heart disease.

This idea forms the backbone of modern dietary guidelines from organizations such as the American Heart Association and the World Health Organization, both of which continue to recommend that people substitute animal fats with vegetable oils like soybean, sunflower, and canola.

Evidence in favor of seed oils largely comes from epidemiological studies and short-term clinical trials. Large population studies have shown that people who consume more polyunsaturated fats tend to have lower LDL levels and, in some analyses, fewer cardiovascular events.

For example, research summarized in the American Heart Association’s 2017 advisory concluded that replacing saturated fats with polyunsaturated fats could reduce coronary risk by as much as 30% — an effect often compared to taking a statin.

Similar findings have been cited in meta-analyses, such as this 2010 study, which reported modest reductions in cardiac events when vegetable oils replaced animal fats in controlled feeding trials. (Let’s just ignore the fact that Mozaffarian’s work was funded by organizations such as the World Health Organization, the Gates Foundation, and several major food industry partners — groups not exactly known for their neutrality in nutritional policy debates).

From a mechanistic standpoint, the argument is equally simple. Polyunsaturated fats contain multiple double bonds, which make them more fluid at room temperature and within cell membranes. This increased fluidity is thought to improve membrane function and vascular flexibility, potentially supporting healthy blood flow and reducing clot formation.

Advocates also point to research showing that polyunsaturated fats, when consumed as part of a balanced diet, can lower triglycerides and may slightly improve insulin sensitivity.

Even the more recent British Journal of Nutrition review (2024) — again, funded in part by several major seed-oil industry groups — reaffirmed this stance, concluding that higher intake of plant-derived unsaturated fats, both monounsaturated and polyunsaturated, is associated with improved lipid profiles and lower cardiovascular mortality.

The authors argued that the benefits outweigh theoretical concerns about oxidation, emphasizing that properly stored and moderately heated oils do not significantly increase markers of oxidative stress or inflammation in controlled settings.

Taken together, the case for seed oils rests on three key pillars: their ability to lower LDL cholesterol (we now know, however, that lower LDL cholesterol does not equal lower CVD), the consistent appearance of positive associations in large population studies, and their long-standing endorsement by public health authorities. For proponents, these factors provide compelling evidence that seed oils are not only safe but beneficial when used in place of traditional animal fats.

The Case Against Seed Oils

If the case for seed oils leans on selective epidemiology and LDL reduction, the case against them rests on chemistry, biology, and an uncomfortable look at what actually happens inside the body — and the population — when these oils replace traditional animal fats.

The Problem with Linoleic Acid

At the heart of the argument is linoleic acid (LA), the dominant omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid in most seed oils. Unlike saturated fats, which are stable and resistant to oxidation, linoleic acid is chemically fragile.

It contains two double bonds that make it highly reactive to heat, light, and oxygen — meaning that from the moment a seed is crushed, LA begins to oxidize. Those oxidation products don’t just disappear when you cook with the oil; they make their way into your body.

Research over the last two decades has shown that oxidized linoleic acid metabolites (OXLAMs) can trigger inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and oxidative stress — all core features of atherosclerosis and chronic disease.

A major review in BMJ Open Heart (2018) described how oxidized linoleic acid accumulates within LDL particles, making them more likely to become oxidized LDL (oxLDL) — a known driver of foam cell formation and plaque buildup in arteries. This “oxidized linoleic acid theory of heart disease” suggests that it’s not cholesterol itself that causes cardiovascular disease, but the instability of the omega-6 fats attached to it.

Lower Cholesterol Doesn’t Mean Better Health

Meta-analyses by Ramsden et al. have reinforced this concern. When researchers re-examined older dietary trials — like the Sydney Diet Heart Study and the Minnesota Coronary Experiment — they discovered something that should have made headlines decades ago: participants who replaced saturated fat with omega-6-rich seed oils saw lower cholesterol but higher mortality, particularly from heart disease.

Yes, that’s right. The more their cholesterol dropped, the higher their risk of death. That’s not exactly the victory story we were sold.

Beyond cardiovascular disease, rodent studies have consistently found that high-linoleic diets promote cancer growth compared with diets rich in saturated fats. Animals fed corn or safflower oil — both high in linoleic acid — show greater tumor incidence and faster growth rates than those fed coconut or hydrogenated oils.

While human data here are limited, the consistency of these findings across multiple tissues and species raises legitimate concern.

Oxidation, Inflammation, and Omega-6’s

Even if we ignore epidemiology, biochemistry alone tells a cautionary story. When unstable polyunsaturated fats are incorporated into cell membranes, they make those membranes weaker and more vulnerable to oxidative damage.

This process generates reactive oxygen species and triggers inflammatory signaling — both of which accelerate aging and disease. Essentially, the fats we eat become the fats we’re made of. If your cells are built from fragile, oxidizable fats, your tissues become fragile too.

Critics of seed oils also point to their omega-6 to omega-3 imbalance. Traditional human diets contained roughly a 1:1 ratio of these fats; today, the average Western diet sits around 15:1 or higher. This imbalance shifts the body’s inflammatory tone toward chronic, low-grade inflammation — a key factor in everything from metabolic syndrome to neurodegeneration.

What History Tells Us – A Century of Declining Health

Beyond the endless debates over clinical data, which often hinge on selective variables and funding bias, stepping back to see the bigger picture helps reveal what’s really going on.

Over the past century, seed oil consumption in the U.S. has exploded — particularly soybean, canola, and corn oil — while saturated fat intake has steadily declined. During that same period, rates of obesity, diabetes, heart disease, autoimmune disorders, and infertility have all soared.

Correlation doesn’t prove causation, but the timing is difficult to ignore. Humans thrived for millennia on diets rich in butter, tallow, and animal fat. The modern health crisis only began after these traditional fats were replaced with industrially refined oils extracted from seeds — foods that no human in history had ever consumed in such quantities.

Before the industrial revolution, people didn’t “press” oil from soybeans or cottonseeds. These were agricultural byproducts — industrial waste — repurposed through new chemical extraction methods using high heat, pressure, and solvents like hexane. The end result was a shelf-stable, low-cost fat marketed as “heart-healthy,” even though its molecular fragility made it anything but.

A simple look at the timeline tells the story:

- 1900: Almost no seed oils in the diet. Heart disease virtually unknown.

- 1950s–1980s: Seed oils replace butter, lard, and tallow as the dominant cooking fat.

- Today: Seed oils make up 20–30% of total daily calories in the Western diet — and chronic disease is the new normal.

While correlation doesn’t prove causation, especially when there are many other factors that likely contribute to this too, such as less exercise and more processed food in general, it certainly demands a closer look — especially when the biological mechanisms for harm are already well understood.

What Biology Tells Us – Back to Nature’s Design

Forget politics for a moment. What does basic human biology say about the fats we’re designed to eat?

The answer is surprisingly simple. Our bodies are built around saturated and monounsaturated fats. Every single cell membrane in your body relies on saturated fats for structure and stability, while using monounsaturated fats (like those found in olive oil and avocados) for flexibility and fluidity.

Polyunsaturated fats — the kind found in seed oils — play a role, but it’s a small one. They’re meant to be minor components, not dominant energy sources. When they make up too large a share of your diet, they replace the stable fats in your cell membranes with fragile ones that oxidize easily, making tissues more vulnerable to damage.

There’s another clue in nature: breast milk. Human breast milk — arguably the most biologically “perfect” food — contains roughly 40–50% saturated fat, around 35% monounsaturated fat, and only a small fraction of polyunsaturated fat. This isn’t a coincidence. Growing infants rely on saturated fat for brain development, hormone production, and immune function. If saturated fat were truly harmful, evolution wouldn’t have built it into the foundation of human nutrition.

Your body also stores fat as saturated fat, not polyunsaturated fat — because saturated fat is stable, compact, and safe. If unsaturated fats were truly healthier, your biology would store energy that way. Instead, it uses what’s most reliable for survival.

In short, the body itself — and the entire natural world — testifies that saturated fats are fundamental, not dangerous. The recent war on them was built on shaky science, and the industrial oils that replaced them may be the real dietary anomaly.

The Financial Engine Behind the Research

If the science seems conflicted, the funding often explains why.

The loudest defenders of seed oils are usually tied, directly or indirectly, to the very industries that produce them. Research supporting “heart-healthy vegetable oils” has been repeatedly funded by organizations like the United Soybean Board, the Canola Council of Canada, and multinational food manufacturers who rely on these oils for cheap, stable products.

By contrast, there’s virtually no comparable funding supporting traditional fats like butter, tallow, or coconut oil. There’s no Big Tallow or National Butter Council bankrolling studies to defend animal fats — those industries don’t have the same lobbying power or financial incentive.

It’s a lopsided playing field, and the result is predictable: studies funded by seed oil producers often emphasize short-term cholesterol reduction, while downplaying long-term oxidative stress, inflammation, and metabolic consequences.

Even some of the most frequently cited meta-analyses, like those by Mozaffarian and colleagues, disclose funding from groups such as the World Health Organization, the Gates Foundation, and major food industry stakeholders — not exactly paragons of neutrality in nutritional policy.

When billions of dollars and global policy narratives are tied to one conclusion, it becomes very difficult for dissenting voices to be heard — even when those voices are backed by solid evidence.

So… Are Seed Oils Bad?

After wading through decades of conflicting research, shifting guidelines, and industrial influence, one thing becomes clear: the debate over seed oils isn’t just about data — it’s about perspective.

If you judge purely by short-term clinical markers like LDL cholesterol, seed oils might seem beneficial. But when you widen the lens — looking at oxidation, inflammation, evolutionary biology, and historical trends — the story changes dramatically.

Seed oils are not poison, but nor are they the “heart-healthy” miracle they’ve been sold as. Their fragility, high omega-6 content, and widespread overuse in processed foods have created a dietary environment our biology was never designed to handle. The evidence increasingly points to oxidized linoleic acid and chronic inflammation as the common threads linking seed oils to modern disease.

Meanwhile, the very fats we replaced — saturated and monounsaturated fats from natural sources like butter, tallow, coconut oil, and olive oil — have supported human health for millennia. Breast milk, cell membranes, and stored body fat all tell the same biological story: nature built us on saturated and monounsaturated fats, not refined seed oils.

So, are seed oils bad for you?

That depends on how you define “bad.” In small, unheated amounts from whole foods like nuts and seeds, they can play a modest role in a balanced diet. But as the foundation of modern processed food — extracted, refined, bleached, deodorized, and oxidized — they’ve almost certainly done more harm than good.

If there’s one takeaway, it’s this: return to the fats nature designed you for. Choose real, minimally processed sources — butter, tallow, ghee, olive oil, and coconut oil — and cut back on industrial seed oils hiding in packaged foods.

Your body, and likely your long-term health, will thank you.

FAQs

What are seed oils, and why are they controversial?

Seed oils — such as soybean, canola, and sunflower oil — are high in omega-6 polyunsaturated fats. They became popular as “heart-healthy” alternatives to animal fats, but growing research links their instability and oxidation to inflammation, metabolic dysfunction, and heart disease.

Are seed oils actually bad for your heart?

Short-term studies show that seed oils can lower LDL cholesterol, but newer meta-analyses reveal no clear heart benefit. Evidence suggests oxidized linoleic acid, the main fat in seed oils, may promote atherosclerosis and inflammation — making their long-term safety questionable.

What are healthier alternatives to seed oils?

Stable fats like butter, tallow, ghee, olive oil, and coconut oil resist oxidation and better match human biology. Using these minimally processed fats for cooking and avoiding industrial seed oils in packaged foods is a safer long-term approach.