The Subconscious Mind – What Is A Subconscious?

The subconscious mind has long been surrounded by mystery, but cognitive sciences are unravelling the mystery.

Why do goals feel so elusive? We all have dreams and aspirations that fill us with tremendous energy, whether that is to become a doctor or to start a business. Turning this motivation into actionable steps, however, is where the majority get lost and ultimately fail.

Often we are our worse own enemy; without adequate tools to plan and accomplish our goals, we will inevitably succumb to our emotional defaults of overwhelm and frustration, inevitably giving up.

If we could just understand the neuroscience behind goal-setting, however, and frame and plan our goals to align with our natural biological drives, we can utilize the neurology of the brain to work with our goals, not against them.

This article aims to draw us closer to this utopia by providing the knowledge of how to set goals that work alongside your complicated neural systems, using “the will” and “the way” to allow you to frame and plan your goals through to completion.

If you have one goal today, make it to read this article thoroughly – the information contained within will change how you plan goals forever.

The brain is an immeasurably complex organ; the gap in knowledge surrounding it is colossal. The brain has an estimated 86 billion neurons, each with over 1000 connections resulting in close to 100 trillion nerve connections (synapses). That’s an unfathomably large number; it is at least 1000 times the number of stars in our galaxy.

Recent brain studies estimate its storage capacity at one petabyte (1 million gigabytes or the equivalent of 1000 computers today), revealing the sheer scale of the problem that must be overcome. Put simply, we are many years away from understanding exactly how the brain works – if ever.

Recent research at the interface of neuroscience and psychology has made significant strides in uncovering the mental processes behind goal-setting and its pursuit. While previously limited to the empirical investigations of psychology, cognitive and social neurosciences have been adopting the field with enthusiasm over the past few decades.

At last, the seemingly mysterious is now becoming increasingly tangible. We are inching closer to discovering the science of success and understanding how to set goals that align with the mechanisms of the brain.

A typical dictionary definition of a goal would focus on any desired end-state that requires intermediate actions to complete. While true by definition, a more helpful description for practical purposes would be any desired outcome that would not naturally occur without manual intervention, requiring a detour from the path of least resistance.

The latter definition captures an important aspect that is missed from the former, that is, a change that would not occur unless we knowingly changed our behavior to overcome an internal resistance (that feeling of discomfort or not wanting to do something, such as procrastination or laziness).

According to the first definition, going to the pub with your friends on a Friday night is a goal; it is an imagined end state for which you took action to complete.

But most would not be too impressed by your resolve to complete this goal because it is likely to happen whether you consciously plan for it or not and without much resistance (we want to go out to drink and socialize).

Our new definition of a goal, however, refers to doing things we want to but have difficulty achieving. Otherwise, we wouldn’t need a goal in the first place.

This sense of effort against an internal resistance, or friction created by the limbic system, is defined as behavioral change. It is the largest source of failure for goals, and no matter how sincere your intentions or competent your skills are, without overcoming this resistance, failure is inevitable.

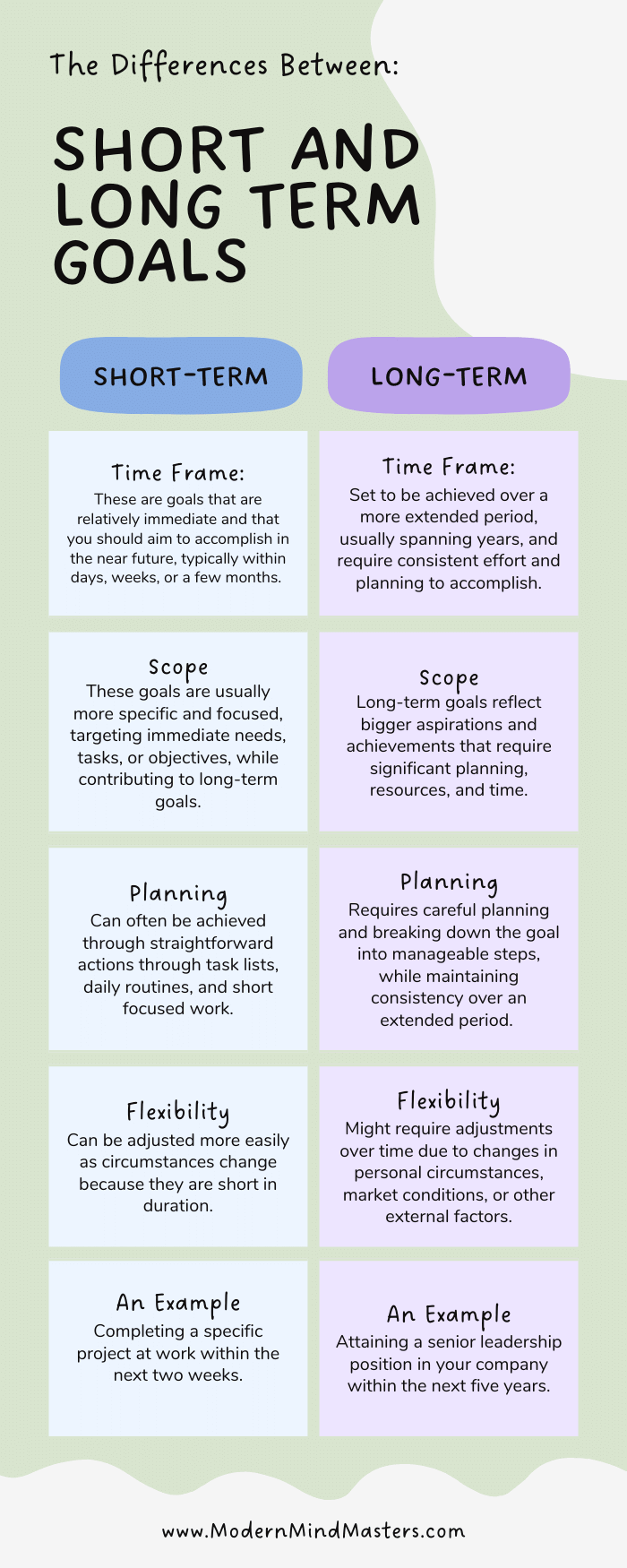

It may seem obvious; short-term goals are tasks or activities you would like to complete immediately, whereas long-term goals a more complex tasks that need to be worked on for weeks, months, or even years. But the time frame is only one difference between the two.

An example of a short-term goal might be completing a specific project at work in the next few days, whereas an example of a long-term goal might be attaining a senior leadership position in your company within the next five years. Whether a goal is short- or long-term not set in stone; it is context specific and dependent on many factors.

Why is this important? Short and long-term goals have different requirements in motivation required to complete them and how we should plan for them. Short-term tasks require less planning but a greater motivation to get up and complete them quickly. Long-term goals, however, require the opposite approach; less emotion and more planning.

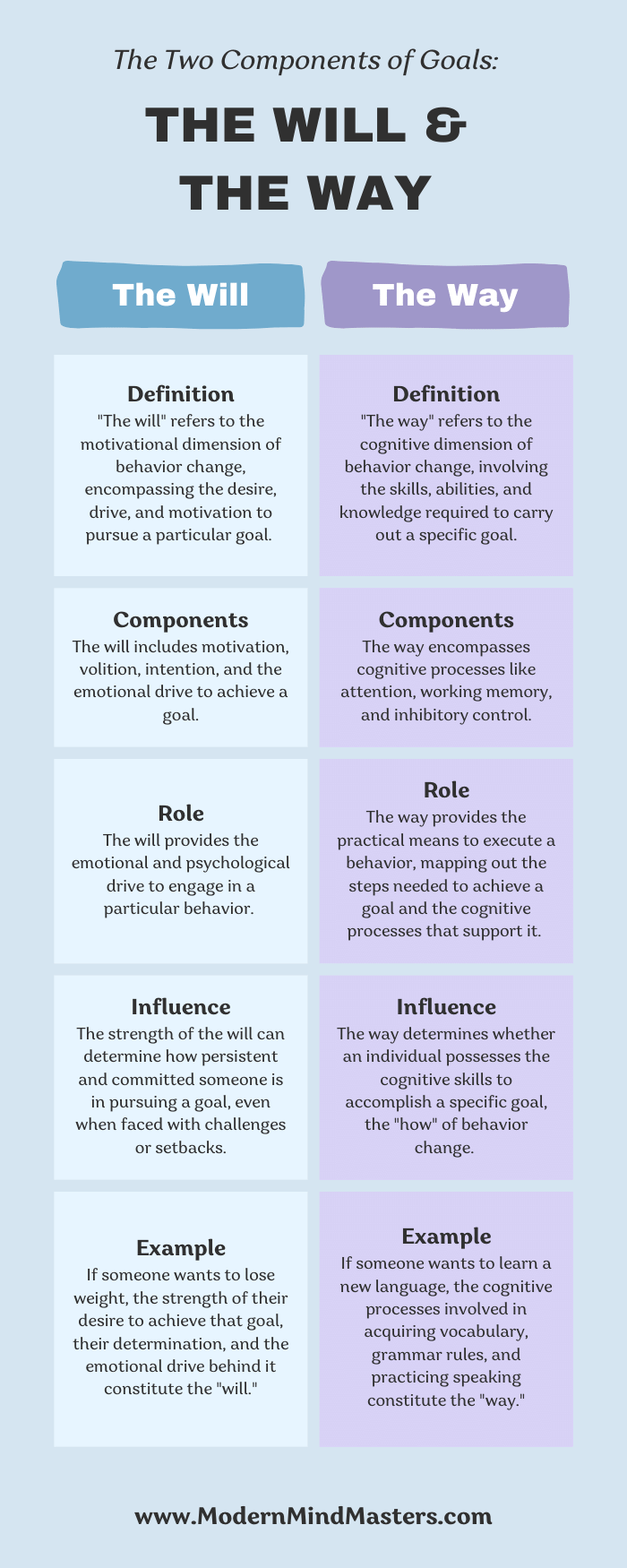

The article “The Neuroscience of Goals and Behavior Change” by Elliot T. Berkman of the University of Oregon articulates a framework that distinguishes behavior change (the basis of goal-setting) into two distinct categories; one motivational (the will) and the other cognitive (the way).

The first dimension, the way, captures the skills and knowledge required to engage in a behavior. It reflects the means and ability to execute a goal through to completion. You might have a colossal motivation and passion to become a pilot, but without the cognitive knowledge of how to (safely) operate an airplane, you won’t be flying far at all.

The second dimension, the will, captures the desire and drive to change. It relates to the motivation to engage in a behavior, including the want to achieve a goal and the willingness to prioritize it over others.

Many feel pressured into going to medical school, having passed all of the exams and cognitive tests required to study, but without the will to become a doctor, they find it difficult to motivate themselves to complete their studies.

Complex behavior, as all worthy goals are, typically requires changes to both dimensions. And when they overlap, four broad types of action emerge.

The type of behavioral change needed to complete a goal is identified by the graph below. The horizontal axis represents an increase in motivational change as it progresses from left to right. The vertical axis represents a change in skill and knowledge as it rises from bottom to top.

This quadrant requires an elevated level of skill or knowledge to complete but little motivation. This is a productive quadrant because it provides little internal resistance while achieving a lot. Habits and habitual behaviors reside in this area where complex behaviors are triggered by external cues and are completed automatically without us having to muster the willpower.

A typical example of this would be driving to work. Many of us commute the same routes to the same destinations frequently enough that we can soon perform it automatically without thinking about it. Here we complete a complex behavior without the conscious goal to do so.

Behavior in this quadrant requires little skill and motivation, containing simple and often repeated behaviors such as walking, eating, and bathing. These actions are so effortless that we don’t think of them as goals at all. Although they contain equally little skill to initiate as the quadrant above, they are distinguished by their skill requirements.

Moving further to the right on the horizontal axis we have simple-novel behavior that does not require much skill but needs motivation. Irregular tasks that are new typically fall into this category, such as changing a diaper for the first time. We know it won’t be pleasant (hence a need for motivation), but the activity is relatively easy.

The behavior of most interest resides in the top-right where both skill and motivational requirements are high. We care the most about these goals because they enable the greatest behavioral change. Becoming a best-selling author or developing an enduringly profitable business are examples that many plan for but fail to accomplish due to a lack of necessary behavior change.

Successfully changing your behavior to meet your goal depends on appropriately navigating the graph (the will and the way as determined by the axes). You must identify the type of change required for your goal (which quadrant you are going to and where you are coming from) and plan actions that will increase them accordingly.

While most inherently understand that motivation is fundamental to change, they fail to identify the skill gap that needs to be bridged.

First-time authors wishing to write their long-planned novel usually know that they need to muster the willpower to write 2000 words a day (the will) but fail to plan for increasing their technical skills, such as creating an adequate structure for the book (the way).

Habits are a key part of behavioral change. They move an action from the right of the graph to the left (that is, from a high motivation to a lower one) while the skill level remains the same. The brain strives for efficiency and can transfer repetitive tasks to the subconscious, freeing up more valuable conscious resources for more pressing tasks.

By placing your goal into its appropriate quadrant, and identifying along which axis you need to move to achieve it (usually increasing in both axes), you can identify where you need to focus your time to adequately change your behavior. From here it is a case of careful planning to increase the motivational and cognitive skills you have just identified.

Fortunately, motivation comes naturally when we align with our goals. Emotion is the primary driver of change and is a natural mechanism for alerting our conscious mind to where it needs to pay attention. Skill, on the other hand, is experiential and can only be obtained by learning and putting your knowledge into practice.

When setting your goals, you need to answer some important questions to identify the obstacles you’re likely to face and how you plan to overcome them. Such questions might be:

These three simple questions will help you identify which quadrant you are currently in and where you need to move to achieve your goal (most goals worth completing are in the top right).

Once your most relevant dimension of change is identified, ask yourself some secondary questions to learn more about the specific nature of motivation or skills that are needed to achieve your goal. Such questions might be:

Let’s put all of this into practice to show how a real-life example might work. Imagine your goal is to start a self-employed business as a financial advisor.

First, plot your position on the graph. Assuming you have never started a business before, doing it for the first time will involve lots of learning. You may know everything you need about financial management, but operating a profitable business requires lots of secondary knowledge.

You will have to learn basic accounting and small business law to legally set up your business without incurring unforeseen tax issues. You will also have to learn the basics of marketing and managing social media to find new clients.

These are the skills you need to learn to overcome the barriers that enable you to move vertically up the graph toward your goal. Having identified these skills, you can now plan for them, such as online courses for accounting and small business management.

Second, identify your motivational requirements. Because the experience is new, it will feel difficult and thus will require a significant amount of motivation. Find your emotional driver for your goal and visualize it.

Call upon it often when you inevitably feel discouraged. Motivation is dependent on dopamine, so ensure you reward yourself sufficiently for every small win and set rewards for completing future tasks.

The key takeaway from this article is to understand the four types of behaviors per the graph and identify where you currently reside and where you need to move to complete your goal.

By identifying quadrants, you determine which axis you need to move along. It will be either motivational (the will), cognitive (the way), or both.

Plan how you will address these required movements. Most goals have a will (internal emotion will provide you motivation if you desire your goal strongly enough), but few plan how they will address the gap in skills and knowledge required to change.

Ask yourself the questions outlined and provide genuine and honest answers. Plan how you will obtain this gap in knowledge and put it into practice, slowly but surely.

Remember, goal-setting is easy; completing them is not. But now you know how to properly set goals that meet the needs of neuroscientific behavioral change, following through just became much easier. Put this into practice and become the valuable human you were born to be.

A typical dictionary definition of a goal would focus on any desired end-state that requires intermediate actions to complete. While true by definition, a more helpful description for practical purposes would be any desired outcome that would not naturally occur without manual intervention, requiring a detour from the path of least resistance.

An example of a short-term goal might be completing a specific project at work in the next few days, whereas an example of a long-term goal might be attaining a senior leadership position in your company within the next five years. Whether a goal is short- or long-term not set in stone; it is context specific and dependent on many factors.

When setting your goals, you need to answer some important questions to identify the obstacles you’re likely to face and how you plan to overcome them. Such questions might be:

The subconscious mind has long been surrounded by mystery, but cognitive sciences are unravelling the mystery.

Emotions stem from the limbic system, an impulsive and primal part of the brain that is extremely powerful. Unfortunately, no one teaches us how to manage emotions, but thankfully these books will.

Higher dopamine levels increase motivation and drive over the short term, but consistent use longer-term will have the opposite effect. Learn the negative effects of increasing your dopamine and how to use it optimally.

Explore how diet, from omega-3s to ketogenic diets, impacts anxiety, offering a holistic approach to mental health through nutritional psychiatry.

Learning from failure is nature’s most efficient learning mechanism, yet as adults, we try to avoid failure at all costs. Instead, we should learn how to fail the correct way.

Perfectionists may be known for their high standards and attention to detail, but perfectionism is the enemy of productivity. It also causes much stress and anxiety.

© 2025 Modern Mind Masters - All Rights Reserved

You’ll Learn:

Effective Immediately: 5 Powerful Changes Now, To Improve Your Life Tomorrow.

Click the purple button and we’ll email you your free copy.