Of all the myths that plague modern nutrition, none is more tragic than the crusade against saturated fat.

Yet I cannot blame anyone for believing it. Dozens of studies have concluded that saturated fat may be harmful to cardiovascular health, or have correlated diets high in saturated fat with increased outcomes of heart disease.

I’m going to set the record straight right now. Saturated fat is not bad for you. Thankfully, better research and studies are now backing this up, alongside the slow but steady easing of saturated fat recommendations from dietary advisement groups.

Yet the myth has proven so persistent that many still question whether saturated fat — and even meat itself — has a place in a healthy diet. This article sets out to clear the confusion by unpacking the myths and the science behind saturated fat: how the fear began, when the evidence shifted, and why saturated fat isn’t just safe — it’s essential for optimal health.

What is Saturated Fat?

Saturated fat, alongside cholesterol, is one of the most misunderstood nutrients in modern health discussions.

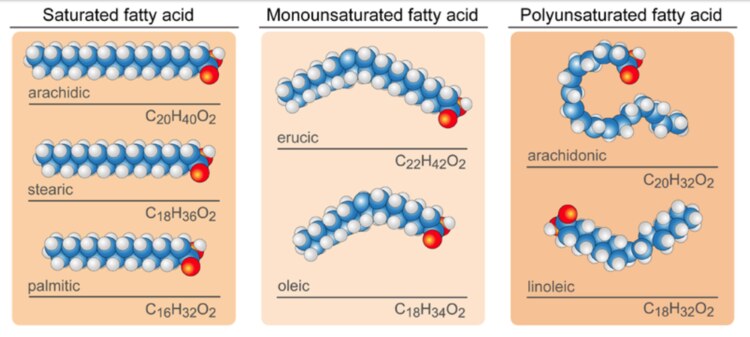

Chemically speaking, saturated fats are made up of fatty acids whose carbon chains are fully “saturated” with hydrogen atoms. This makes them incredibly stable — thanks to strong single bonds between the carbon atoms — and that stability is exactly why saturated fats tend to stay solid at room temperature. Foods like butter, coconut oil, cheese, and animal fats are all naturally high in saturated fat.

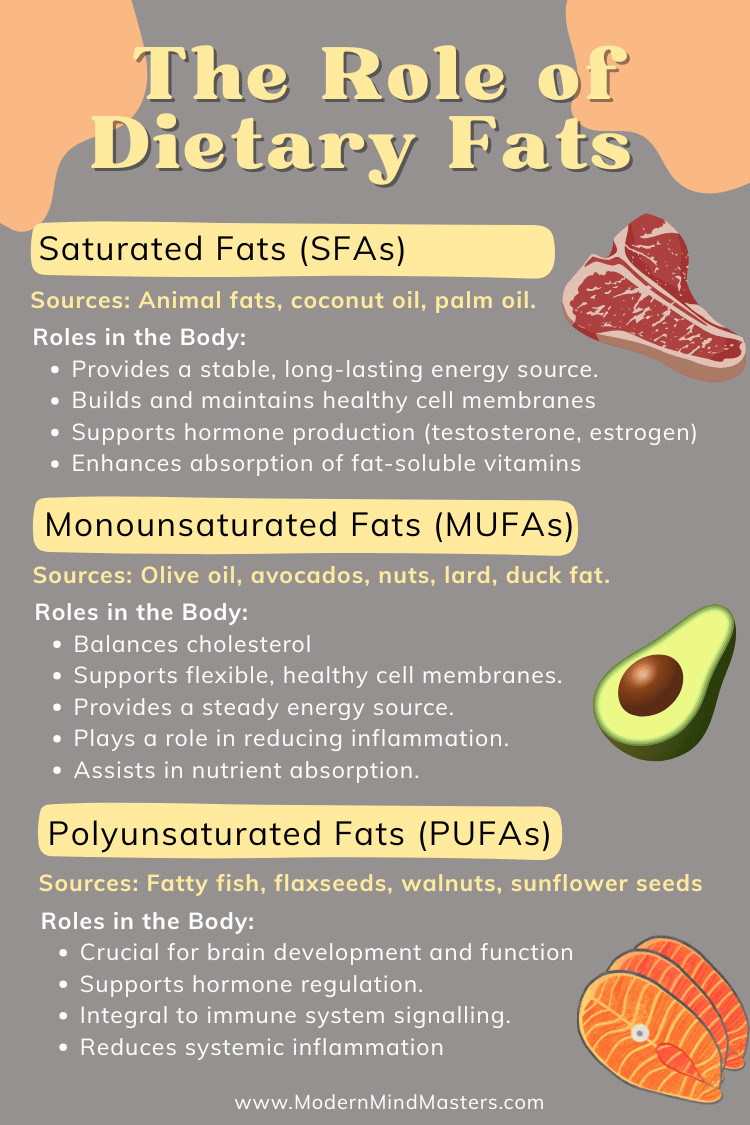

Now, not all fats behave the same way. Fats are usually classified into three types: saturated fatty acids (SFAs), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). The key difference is in their molecular structure.

Monounsaturated fats (the kind you’ll find in olive oil and avocado) have one weak double bond that creates a bend, making them liquid at room temperature. Polyunsaturated fats, like those found in seed oils and fish, contain multiple double bonds and multiple “kinks,” which makes them the most fragile and prone to oxidation, especially when heated or exposed to light.

Each type of fat plays a specific role in your body, and it’s a mistake to assume one is inherently “good” or “bad.” In fact, the majority of the fat stored in your own body is saturated fat — not because of poor dietary choices, but because your biology is designed to work that way.

Why Do We Need Saturated Fat?

Saturated fat isn’t just a convenient energy source — it plays several essential roles in the human body, and nature designed us to rely on it.

Unlike unsaturated fats, which remain liquid and are perfectly suited for tasks like lubricating joints (in the form of synovial fluid) and keeping our eyes moist (via tears), saturated fats are denser and sturdier. This makes them ideal for other critical jobs, like insulating us from the cold, protecting our internal organs from damage, and — perhaps most importantly — serving as a compact, flexible, and highly efficient form of energy storage.

In fact, fat holds more than twice the energy per gram compared to carbohydrates like starch. That’s especially important because energy-hungry organs like your muscles, heart, and brain burn through fuel far faster than the more stationary parts of the plant world — where energy is usually stored as starch.

Our bodies, on the other hand, don’t have the luxury of storing much carbohydrate at all. Once your limited glycogen reserves are full, any extra carbohydrates you eat get converted by your liver into saturated fat for long-term storage.

When your body tucks away extra fuel, it doesn’t turn it into unsaturated fat — it turns it into saturated fat. If saturated fat were inherently dangerous or unhealthy, it’s very unlikely evolution wouldn’t have hardwired this system into our biology.

And there’s a good reason for this: saturated fat is compact, stable, and doesn’t cause your tissues to sag or break down the way a body full of unsaturated fat would. Think of saturated fat as the sturdy, reliable fuel your body trusts to get you through the next period of scarcity — which is exactly why it’s so important for survival.

Beyond storage, saturated fats also help strengthen cell membranes, balance hormone production, fuel the immune system, and ensure your body runs smoothly from day to day. Saturated fat isn’t just safe — it’s essential.

Why is Saturated Fat Seen as Bad?

The billion-dollar question.

For decades, saturated fat has been painted as the villain behind clogged arteries, heart attacks, and rising cholesterol levels. It’s a narrative so deeply rooted in modern nutrition advice that most people accept it as fact. But the truth is — this story was built on shaky foundations from the very start.

The roots of the myth go back to the 1950s when a scientist named Ancel Keys proposed what became known as the Diet-Heart Hypothesis. His theory was simple: saturated fat raises cholesterol, and high cholesterol causes heart disease. It was a neat and tidy explanation, and it quickly gained traction in both the medical world and the public eye.

To back up his claims, Keys conducted the now-famous Seven Countries Study, which appeared to show a direct link between saturated fat intake and heart disease rates across several nations. The study became the cornerstone of modern dietary guidelines, shaping the way we’ve thought about fat for the better part of a century.

But there was a catch — and it was a big one.

Out of the full set of data from 22 countries, Keys only included the 7 countries that neatly fit his hypothesis. He conveniently left out nations like France, where people consumed plenty of saturated fat but had surprisingly low rates of heart disease (a phenomenon now called the French Paradox).

Despite these glaring flaws, the U.S. government ran with Keys’ conclusions. When the first U.S. Dietary Guidelines were published in 1980, they warned Americans to limit saturated fat and cholesterol to avoid heart attacks and obesity. Foods like eggs, butter, and red meat were pushed aside, while low-fat, high-carb diets became the new gold standard for “healthy eating.”

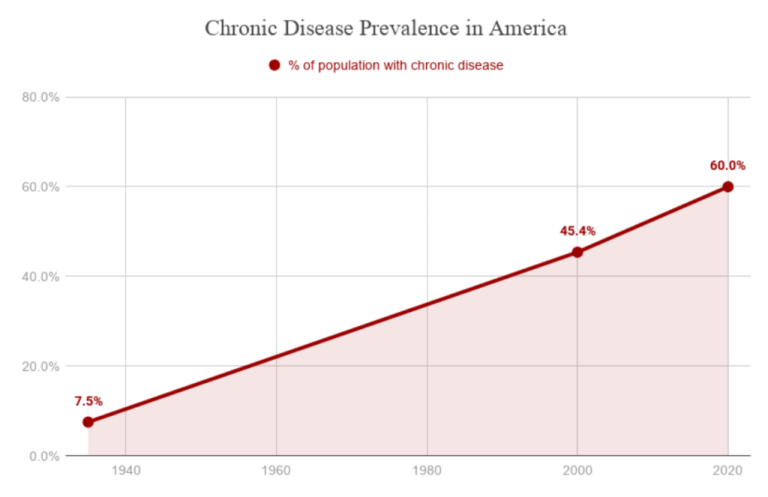

Coincidentally, this turn away from whole animal foods towards industrialized foods also marks the start of the Western health epidemic.

Food manufacturers quickly capitalized on this shift. Grocery store shelves were flooded with fat-free cookies, low-fat yogurts, cholesterol-free margarine, and vegetable oils — many of which were heavily processed and far more harmful than the natural fats they replaced.

And so began a perfect storm: a mix of industrial food production, anti-animal fat sentiment, and fear-driven guidelines that would shape global eating habits for generations. Countries around the world followed America’s lead, and the result was a worldwide shift away from traditional whole foods like eggs, butter, and fatty cuts of meat — and toward ultra-processed, carb-heavy, seed oil-laden “health” foods.

The irony? As saturated fat intake declined and ultra-processed foods became the norm, rates of obesity, diabetes, and heart disease skyrocketed.

In the end, the “saturated fat is bad” myth wasn’t born out of solid science — it was born out of cherry-picked data, misguided policy, and a food industry eager to profit from the fear.

What Does the Science Now Say?

So if saturated fat isn’t the villain it’s been made out to be, what does the research actually show?

For years, the idea that saturated fat causes heart disease was treated as settled science. But in recent decades, as more high-quality research has emerged, that old belief has started to crumble. And it’s not just a few isolated studies — we’re talking about the gold standard in research: large-scale meta-analyses and systematic reviews.

Let’s take a look.

A landmark 2010 meta-analysis published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition reviewed 21 studies involving over 350,000 people. The conclusion? There was no significant evidence to support the idea that saturated fat is linked to a higher risk of heart disease or cardiovascular problems.

In 2014, another extensive review was published in the Annals of Internal Medicine. After examining data from 72 separate studies, the authors came to a similar conclusion:

“Saturated fat is not associated with an increased risk of heart disease.”

Fast forward to 2020, when the Journal of the American College of Cardiology published a major review of the evidence surrounding saturated fat and heart health. Once again, the findings were clear: there’s no convincing proof that reducing saturated fat lowers heart disease risk or leads to a longer life.

That same year, an international panel of experts — including two former members of the U.S. Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee — carefully reviewed the research and reached the same verdict: there’s simply no solid scientific justification for capping saturated fat intake at 10 percent of daily calories, a recommendation that has shaped American nutrition policy for decades.

Even global health authorities are adjusting their stance. In 2021, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) revised its heart health guidelines, quietly stepping away from singling out saturated fat as a culprit. Instead, the focus shifted toward the real problem: ultra-processed foods, regardless of whether they’re high in fat or not.

And if that wasn’t enough, the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition also published a strong editorial in 2020 challenging the old anti-saturated fat narrative:

“There is no robust evidence to justify current limits on saturated fat intake for heart health.”

Again, these are not cherry-picked epidemiological studies, with cherry-picked conditions and weak correlations, but large meta-analyses covering hundreds of studies collectively.

When is Saturated Fat Bad?

So when is saturated fat a problem? The answer has less to do with the fat itself — and everything to do with where it comes from.

Saturated fat in its natural form, from whole foods like beef, butter, eggs, cheese, coconut oil, and even breast milk, is a nutrient-dense, highly stable fat that the human body has relied on for millions of years. These foods come packaged with other essential nutrients, in forms your body knows exactly how to handle.

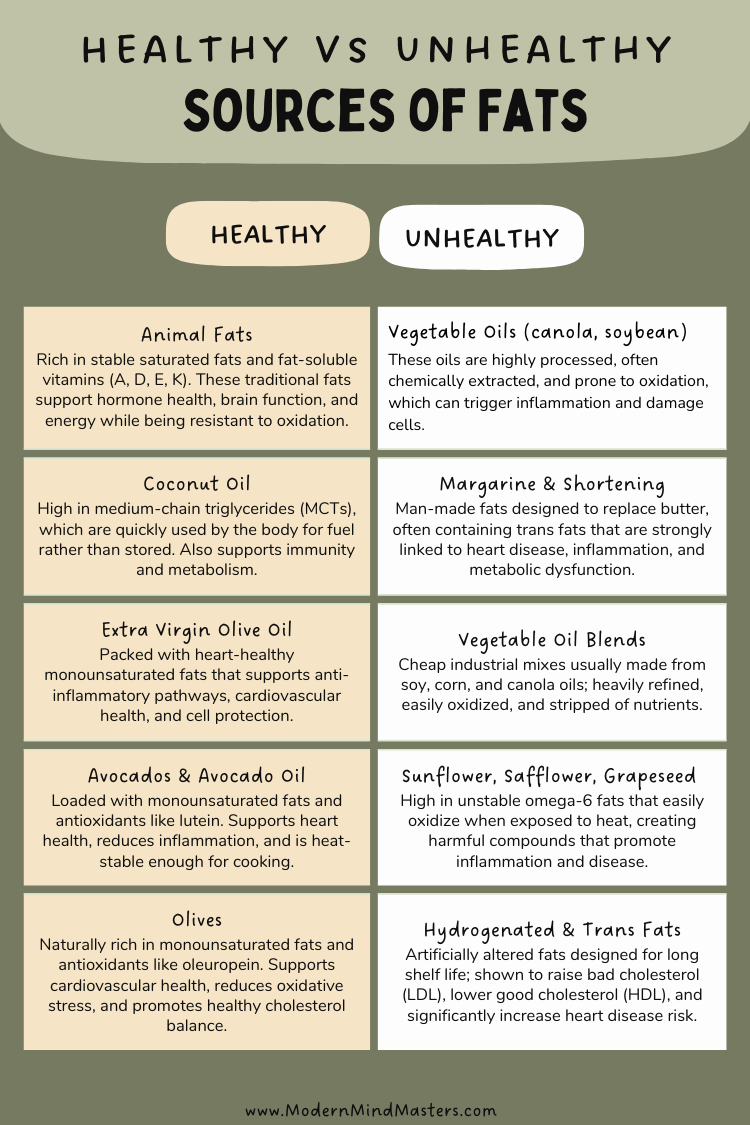

The real danger shows up when saturated fat (or any fat, for that matter) is consumed as part of heavily processed, artificial, or ultra-refined foods, especially deep-fried fast food cooked in low-grade oils, hydrogenated fats found in baked goods and packaged snacks, and processed meats full of additives and preservatives.

In these cases, the problem isn’t the saturated fat itself — it’s the chemical cocktail of damaged fats, inflammatory additives, excess refined carbohydrates, and highly oxidized oils that typically come along for the ride. It’s this processed food environment, not the naturally occurring saturated fat, that has been repeatedly linked to modern health issues like obesity, heart disease, and metabolic dysfunction.

So it’s not about cutting out saturated fat, it’s about cutting out processed food. When your diet centers around whole, minimally processed foods — especially animal products raised the way nature intended — saturated fat isn’t something to fear. It’s something your body can thrive on. Many of the studies that correlated saturated fat to negative outcomes sourced it from processed food. Of course the result was negative!

Why is Saturated Fat Essential?

It’s easy to get lost in studies, which — especially in the multi-faceted world of nutrition — can be speculative and unreliable for real-world use. So let’s take a look at some biology.

Human Health has Evolved Around Animal Fats and Proteins

For most of human history, saturated fat wasn’t just a part of the diet — it was a prized source of nutrition. Hunter-gatherer societies actively sought out fatty cuts of meat, nutrient-rich organs, and marrow, all loaded with saturated fat and essential fat-soluble vitamins like A, D, E, and K.

Our bodies evolved to digest, absorb, and use these fats efficiently — not just for survival, but for optimal health. In fact, carnivores in the wild, such as lions, birds, wolves, and bears, often prioritize the organ meats first — especially the liver which is nutrient-packed.

So what’s changed? If red meat and saturated fat have been on the human menu for millennia, why are chronic diseases like obesity, heart disease, and dementia more common than ever?

The real culprits aren’t the foods we’ve eaten for thousands of years — they’re the ultra-processed newcomers. These processed ingredients are the defining staples of the modern Standard American Diet (SAD), and both are known to fuel oxidative stress and chronic inflammation — two key players in everything from metabolic dysfunction to mental health disorders.

For decades, vegetable oils were marketed as “heart-healthy” alternatives to animal fats, simply because they’re low in saturated fat and cholesterol. But more and more research is now challenging this claim, raising serious questions about the long-term health effects of these heavily processed oils.

Ultimately, the problem isn’t meat or saturated fat, it’s the modern processed food environment we’ve created around them.

The Role of Saturated Fat in Cellular Structure

Saturated fat isn’t some foreign threat your body needs to fear — it’s literally part of you. Every single cell in your body is wrapped in a protective membrane made from a blend of saturated and unsaturated fats. Saturated fats give these membranes their strength and stability, while unsaturated fats provide the flexibility and fluidity cells need to function properly.

This balance is especially important in the brain. Ever wonder why the brain is so rich in fat? The answer lies in its structure. The brain’s communication network is built on myelin — a fatty, insulating sheath that wraps around nerve fibers like electrical tape around a wire. Myelin is mostly made of tightly coiled membranes, which rely on saturated fats to maintain their shape and durability.

In fact, your brain’s white matter contains more than 60,000 miles of myelinated axons, and none of that would be possible without the structural support provided by saturated fat. Beyond the brain, saturated fats also play critical roles in hormone production and immune defense. To repeat, these are essential, not optional.

Breast Milk is Nature’s Endorsement of Saturated Fat

One of the most powerful clues that saturated fat is essential for human health can be found in the very first food we’re designed to consume: breast milk.

Human breast milk is naturally rich in saturated fat — making up roughly 40–50 percent of its total fat content (as well as around 35% monounsaturated fat and 15% polyunsaturated fat).

That’s not a coincidence. Growing babies rely on saturated fat as a dense and efficient source of energy and as a critical building block for brain development, hormone production, and immune system function.

Why is saturated fat so prominent? Because a newborn’s body is growing at lightning speed, especially the brain, which is about 60 percent fat by dry weight. The fats in breast milk — especially saturated fats and cholesterol — are essential for developing healthy cell membranes, forming myelin sheaths (the insulating layers around nerves), supporting hormone production, and laying the foundation for a strong immune system.

If saturated fat were truly harmful, it would make little evolutionary sense for breast milk — the single most perfect and natural food for human infants — to be loaded with it. On the contrary, nature seems to have designed it that way for a reason: to help us grow, develop, and thrive.

The Cholesterol Misunderstanding

The “saturated fat = heart disease” theory was largely based on early studies that observed a rise in blood cholesterol when people ate more saturated fat. But the problem is, total cholesterol isn’t a reliable predictor of heart disease.

Your body tightly regulates cholesterol levels, and the type and size of cholesterol particles matter much more than the total number — something early studies didn’t account for.

Yet people still commonly associate high-cholesterol foods with unsaturated fat.

This is wrong on two counts. Firstly, saturated fat and cholesterol are two completely different substances, though they often appear together in the same foods. Secondly, cholesterol, similar to saturated fat, is also unfairly demonized in many of the same ways (that’s a whole other topic for a different article).

Cholesterol is a hard, waxy substance essential for all animal life. We can’t build hormones like estrogen, testosterone, or vitamin D without cholesterol, and its mandatory presence in our cell membranes should be comforting to us all, as its sturdy constitution contributes firmness and helps maintain its structural integrity. People often utter the words “fat” and “cholesterol” in the same breath, but not only do they look nothing alike, they serve very different purposes.

Saturated fat is easily chopped up and burned for energy, but cholesterol is indestructible. The only way to dispose of excess cholesterol is to send it to the liver to be turned into bile and excreted by the bowel.

Since many animal-based foods (eggs, cheese, butter, red meat, liver) naturally contain both saturated fat and cholesterol, early research assumed:

High saturated fat + high cholesterol in food → High cholesterol in blood → Heart disease.

But more recent science shows the story is much more complex.

- Dietary cholesterol has little effect on blood cholesterol in most people (your liver produces ~75-80 percent of your body’s cholesterol on its own).

- Saturated fat does influence blood cholesterol, but it tends to raise both LDL and HDL, and not all LDL is equally dangerous. Particle size, inflammation, and metabolic health play bigger roles.

Since every single cell in your body contains cholesterol, it’s clear that cholesterol in itself is not something we should be seeking to avoid. In fact, studies have shown that many vegans have cholesterol levels equal to meat eaters, a result of the body’s ability to make its own cholesterol as it deems necessary.

Your liver produces around 75 percent of your circulating cholesterol, adjusting production up or down depending on how much you consume through food. Once again, if cholesterol were inherently harmful, nature wouldn’t have hardwired it into the core of human biology — or tasked the liver with producing it on demand.

All the body requires is good quality whole meats and animal foods, not processed meats, and it will take care of everything else as it deems necessary.

Final Thoughts

For decades, saturated fat has been wrongly demonized — not because the evidence was solid, but because flawed research, industrial food interests, and outdated policy wove a myth so persistent that it shaped global health advice for generations.

But as modern research continues to catch up, the truth has become clear: saturated fat, especially from whole, unprocessed foods, isn’t the enemy. It’s an essential nutrient that your body not only tolerates but was designed to thrive on. From your brain and hormones to your immune system and cell structure, saturated fat plays a fundamental role in keeping you alive and healthy.

The real danger to human health isn’t natural saturated fat — it’s the highly processed, industrialized food environment that replaced it. Ultra-refined seed oils, engineered snacks, and carb-heavy junk foods have done far more to damage global health than real butter, steak, or eggs ever could.

So the next time you see saturated fat on your plate — especially if it’s part of a whole, nutrient-dense food — you can drop the guilt. Your biology knows exactly what to do with it. After all, nature built you that way.

FAQs

Is saturated fat good or bad for you?

Each type of fat plays a specific role in your body, and it’s a mistake to assume one is inherently “good” or “bad.” In fact, the majority of the fat stored in your own body is saturated fat — not because of poor dietary choices, but because your biology is designed to work that way.

What are the healthiest fats to eat?

Saturated fat in its natural form, from whole foods like beef, butter, eggs, cheese, coconut oil, and even breast milk, is a nutrient-dense, highly stable fat that the human body has relied on for millions of years. These foods come packaged with other essential nutrients, in forms your body knows exactly how to handle.

The real danger shows up when saturated fat (or any fat, for that matter) is consumed as part of heavily processed, artificial, or ultra-refined foods, especially deep-fried fast food cooked in low-grade oils, hydrogenated fats found in baked goods and packaged snacks, and processed meats full of additives and preservatives.

Are animal fats good for you?

It’s not about cutting out saturated fat, it’s about cutting out processed food. When your diet centers around whole, minimally processed foods — especially animal products raised the way nature intended — saturated fat isn’t something to fear. It’s something your body can thrive on. Many of the studies that correlated saturated fat to negative outcomes sourced it from processed food.