8 Easy Habits for a Healthier Lifestyle

Small changes, big impact. These ten science-backed habits boost your health, energy, and longevity.

For decades, we’ve been told that high cholesterol, especially LDL (Low-Density Lipoprotein), is the main cause of heart disease. Yet this is not what modern science and gold-standard meta-analyses have found. Research over the past decade has turned that belief on its head.

In fact, the consistent lack of any link between total cholesterol and heart disease has forced many health authorities to stop recommending limiting saturated fat or cholesterol containing foods, such as 2015–2020 U.S. Dietary Guidelines dropping the limit on dietary cholesterol entirely.

Unfortunately, many doctors have not kept up with the changing landscape and are still recommending avoiding cholesterol foods, and even worse, automatically prescribing statins without further testing.

Statins aren’t all bad, however. While their side effects are often downplayed, they do serve some benefits in certain populations, specifically middle-aged men who have already had some form of heart event. But the benefits of statins are not from lowering cholesterol, as we will see.

The real threat to our hearts? Oxidized LDL. Cholesterol is damaged by inflammation, processed foods, and sugar, not cholesterol itself.

In this article, we’ll break down the myths surrounding cholesterol, explain what actually increases heart disease risk, and explore why statins might not be the magic bullet they’re made out to be.

Let’s start with the big one: that cholesterol leads to heart disease. The assumption was so profound that it had its own name – the diet-heart hypothesis. And a hypothesis is all that remains – hundreds of studies later, and there is still no correlation between cholesterol serum (blood) levels and heart disease.

The myth started due to Ancel Keys’ Seven Countries Study between 1958–1970. The now infamous observational study looked at diet and heart disease rates in seven countries (which were cherry-picked from 22 countries, not including France, which consumed lots of saturated fat but had excellent heart health).

Through questionable methods now considered unethical and scientifically flawed, he concluded that countries with higher saturated fat consumption had more heart disease. Thus was born the belief that saturated fat raises cholesterol, which in turn causes heart disease.

Fortunately, more modern and inclusive meta-analyses have not been able to replicate this relationship between cholesterol serum levels and heart disease, and consistently show no correlation.

The Lyon Diet Heart Study asked a simple but powerful question: Can diet alone help prevent heart problems after a heart attack? The results challenged everything we thought we knew about cholesterol and heart disease.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/01.cir.103.13.1823

Researchers followed people who had already suffered a heart attack and split them into two groups. One group adopted a Mediterranean-style diet, rich in fruits, vegetables, nuts, fish, olive oil, and omega-3-rich margarine. The other followed a typical low-fat Western diet, which was considered “heart-healthy” at the time.

The Mediterranean group saw massive improvements:

And these benefits lasted for years.

The unexpected finding was that cholesterol levels didn’t change much between the two groups. Total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels stayed roughly the same. The Mediterranean diet clearly helped, but not by lowering cholesterol.

Instead, researchers pointed to other factors: omega-3 fats, antioxidants, and anti-inflammatory nutrients in whole foods, compared to the processed foods, refined carbohydrates, and sugars from those on the typical Standard American Diet (SAD). These likely reduced inflammation and improved overall heart function, without needing to alter cholesterol levels.

It’s worth noting the context. All participants were recovering from heart attacks and had been eating poorly. So, yes — the Mediterranean diet was a major upgrade. It’s far more likely that simply eating whole foods and avoiding unnecessary and inflammatory processed foods was responsible for the majority of the improvements.

Interestingly, the New England Journal of Medicine refused to publish the study. It eventually appeared in The Lancet, another top journal, but the initial rejection raises questions about how inconvenient findings are sometimes sidelined.

These findings become even more compelling when we look at large-scale data from Japan.

In one meta-analysis, researchers examined over 150,000 participants from five high-quality studies published after 1995. Subjects were grouped by total cholesterol: under 160 mg/dL, 160–199 mg/dL, 200–239 mg/dL, and over 240 mg/dL. According to mainstream guidelines, the lowest cholesterol group should have had the best outcomes, and the highest the worst.

But the exact opposite happened. The lowest cholesterol group had the highest overall mortality. Those with cholesterol between 160 and 239 mg/dL—levels often labeled “borderline high”—did just fine. And high cholesterol wasn’t the death sentence it’s often made out to be.

This wasn’t a one-off finding. In the Isehara Study, based on over 21,000 adults from a city in Japan, researchers grouped people by LDL cholesterol levels—from under 80 mg/dL to over 180 mg/dL. The group with the lowest LDL (<80 mg/dL) had the highest death rates, in both men and women. While men with very high LDL (>180 mg/dL) did see slightly higher rates of heart disease, women didn’t follow the same trend. In fact, women with the highest LDL had the lowest rates of heart disease deaths.

These results were so significant that in 2007, the Japan Atherosclerosis Society stopped using total cholesterol as a clinical marker in its national guidelines. The data simply didn’t support it.

Together with the Lyon Study, the Japanese research reinforces a critical point: cholesterol, especially total and LDL, is a poor predictor of mortality. Low levels don’t guarantee protection—and in many cases, may actually increase risk.

This raises an uncomfortable but necessary question: If lowering cholesterol doesn’t reduce deaths, why is it still the central focus of modern cardiology?

It seems we have an answer: more and more studies are clearly demonstrating that the real initiators of damage in the arteries were oxidation and inflammation, not healthy cholesterol.

Decades of research and billions of dollars have been spent trying to prove that LDL cholesterol causes heart disease. Despite the investment, a direct and consistent link remains elusive. What the research did uncover, however, is that not all LDL is the same, and lumping it all together under a “bad” label has led to misleading conclusions.

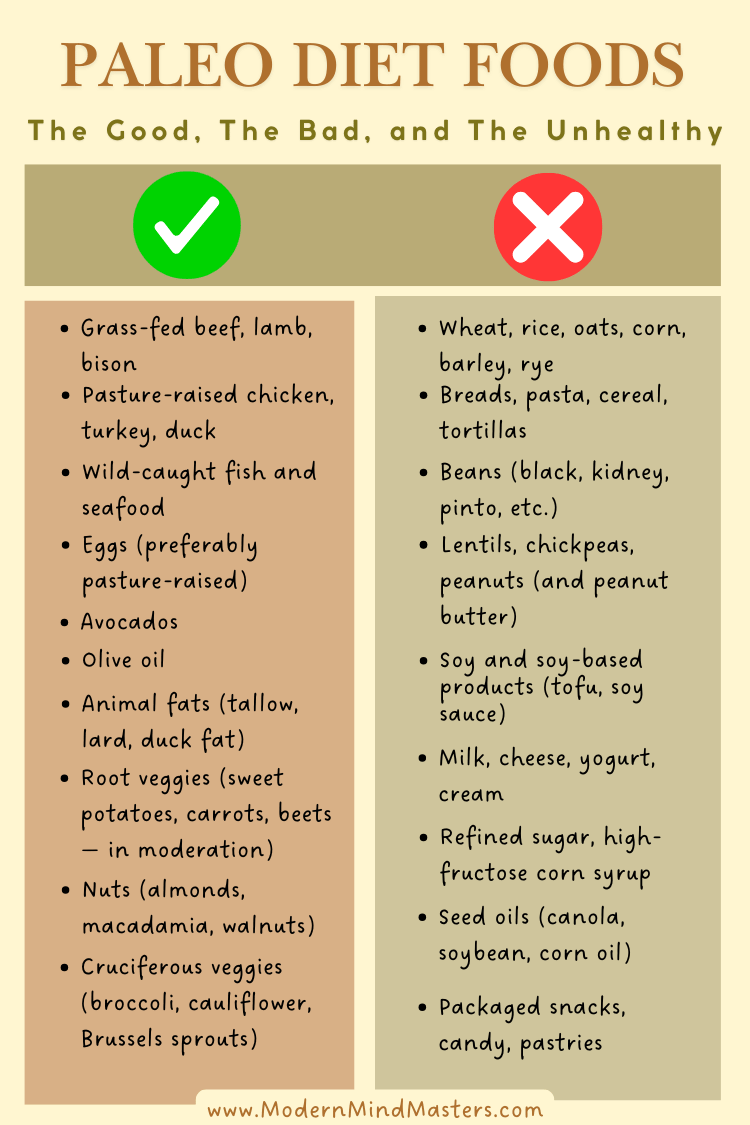

Scientists have identified two main types of LDL particles:

The tragic irony here is that diets long recommended to reduce heart disease, like those low in fat and high in carbohydrates, actually increase the harmful small and dense LDL. Meanwhile, saturated fat, long demonized in heart health guidelines, actually reduces these dangerous particles and promotes the larger, fluffier (and safer) kind. And yet, LDL-lowering drugs (like statins) reduce all LDL particles indiscriminately, including the beneficial ones.

The blind focus on LDL targets continues despite conflicting data. In a study of nearly 140,000 patients hospitalized for heart disease, almost half had LDL levels under 100 mg/dL—the very threshold considered “ideal” by current medical guidelines. Rather than question the validity of LDL as a marker, researchers instead concluded that the target number must be too high. This kind of thinking reflects a troubling resistance to re-evaluate outdated assumptions.

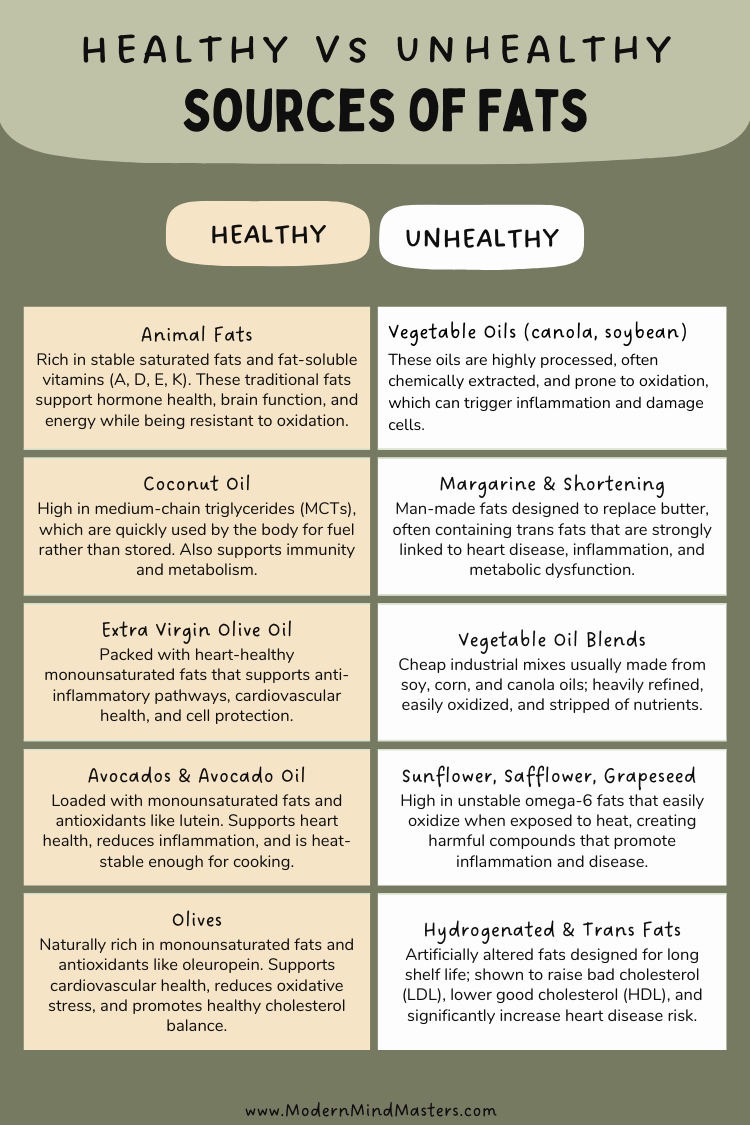

What truly drives heart disease isn’t LDL in isolation—it’s inflammation, oxidation, and insulin resistance. LDL only becomes problematic when it’s oxidized—damaged by free radicals—at which point it can trigger an inflammatory cascade and lead to plaque buildup.

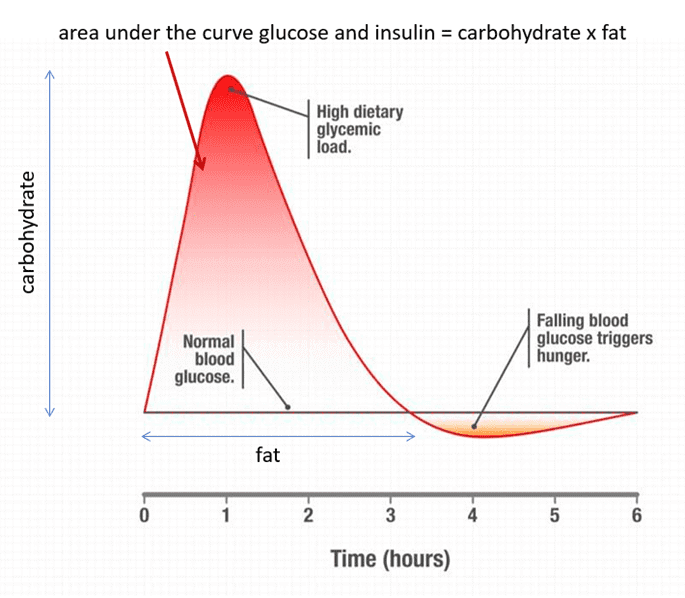

This connects to another crucial point: insulin resistance may be the primary driver of heart disease. One recent analysis found that simply preventing insulin resistance in young adults could prevent 42% of heart attacks.

In short, LDL isn’t inherently harmful, and lowering it without context may do more harm than good. The real issue lies in what’s damaging the LDL in the first place—and that’s where inflammation, poor metabolic health, and ultra-processed diets come in.

For decades, the public was told to avoid cholesterol-rich foods like eggs, butter, and shrimp under the assumption that eating cholesterol would raise blood cholesterol and, in turn, increase heart disease risk. But nutritional science tells a different story.

In reality, dietary cholesterol has little to no impact on blood cholesterol levels for the vast majority of people. Controlled clinical studies have shown that there is not a direct correlation between cholesterol intake and blood cholesterol because the body tightly regulates cholesterol levels: when dietary intake goes up, the liver produces less cholesterol to maintain balance, and when intake goes down, the liver ramps up its production.

Even in people who are more sensitive to dietary cholesterol (a small genetic minority), the changes in blood cholesterol are usually modest and don’t translate into increased cardiovascular risk.

This understanding is now reflected in official guidelines. In 2015, the U.S. Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee removed its longstanding limit on dietary cholesterol, stating explicitly that “cholesterol is not a nutrient of concern for overconsumption.”

Furthermore, foods high in cholesterol—such as eggs and shellfish—are often rich in essential nutrients like choline, B vitamins, and antioxidants, and have not been shown to increase heart disease risk in well-conducted studies.

Decades ago, studies found that saturated fat could raise LDL cholesterol levels, which were thought to be the primary driver of heart disease. But we now know that not all LDL is the same.

There are many different types of saturated fat, such as long, medium, and short, so saying all saturated fatty acids are bad is like comparing Portugal to the whole of Europe. There’s simply not enough context.

Saturated fat tends to raise large, fluffy LDL particles, which are far less harmful than small, dense LDL particles that are more strongly associated with cardiovascular risk. In fact, this type of cholesterol is vital for many crucial bodily functions, especially hormone regulation and cognitive function.

Moreover, saturated fat often raises HDL (the “good”) cholesterol and improves the ratio of total cholesterol to HDL, a better predictor of heart health than LDL alone. In other words, saturated fat may shift cholesterol profiles in a protective direction rather than a harmful one.

The outdated idea that “saturated fat = high cholesterol = heart disease” ignores decades of more nuanced research. As the JACC review concluded, focusing on the type and quality of fat and the overall dietary context is far more important than singling out saturated fat as a villain.

Poor sources of fat, as with any poor quality sources of any food, can increase the oxidation of LDL cholesterol through high quantities of linoleic acid, which has been shown to increase the severity of coronary atherosclerosis.

One study showed that a diet enriched with linoleic acid increased the oxidation of the small, nasty LDL particles, precisely the cholesterol particles that are most dangerous and most involved in the formation of arterial plaque.

Stick with whole foods and grass-fed animal fats, and you’ll be fine. Steer clear of grain-fed meat, vegetable oils (high in oxidizing PUFAs), and processed meats, and you’ll get the best quality nutrients with the lowest risk of oxidized LDL.

Statins are widely prescribed to lower cholesterol levels and reduce the risk of heart attacks. But the idea that statins are a one-size-fits-all solution to heart disease is a myth—and a dangerous oversimplification.

While statins may offer benefits to certain groups—such as middle-aged men who’ve already had a heart attack, coronary intervention, or clear signs of coronary artery disease—their use in the broader population is far more controversial.

One of the major concerns with statins is that they deplete coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10)—a vital compound needed for energy production in cells, especially in the heart. There is a tragic irony here in that a drug meant to protect the heart can actually impair its ability to pump efficiently by depriving it of the fuel it needs. Fatigue, muscle pain, and low energy are common side effects of statin use, and CoQ10 depletion is a likely reason why.

Beyond side effects, the overall impact of statins on long-term mortality is murky. A critical report titled Cholesterol Treatment: A Review of the Clinical Trials Evidence revealed that although statins reduced cardiovascular deaths in some cases, they were often accompanied by a rise in non-cardiovascular deaths, leading to no significant reduction in total mortality. As the authors noted, this troubling pattern is “at the core of much of the controversy on cholesterol policy.”

Re-analysis of major studies like the MRFIT trial (Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial) by researcher David Diamond further highlights the issue. When you strip away the relative risk numbers and look at the absolute risk reduction, the actual benefit of statins in many cases amounts to as little as 1%.

The ALLHAT study conducted between 1994 and 2002 tested the statin drug pravastatin on 10,000 participants with high LDL. The results seemed good – 28% of users did lower their cholesterol (compared to 11% who also did so through lifestyle changes).

But when the death rates from heart attack were examined, there was no difference between the two groups. Although the statin drug lowered cholesterol, it did not reduce fatal or nonfatal coronary heart disease, suggesting that the two are not correlated.

Another study, the Heart Protection Study (HPS), divided 20,000 adults with either coronary artery disease or diabetes into two groups and gave one group 40mg of the statin Zocor.

The study claimed a significant relative risk reduction for statin users. But looking at the absolute numbers, those in the Zocor group had an 87.1% survival rate after five years, compared to the placebo group, who had an 85.4% survival rate – an absolute difference of 1.8%.

While even this modest rise is great, the survival rates were independent of lowering cholesterol, meaning that statins can decrease cholesterol, but this does nothing to affect rates of heart disease.

Statins are not inherently evil, but they are overprescribed. In his excellent book “The Great Cholesterol Myth”, Jonny Bowden argues that statins have been shown to benefit middle-aged men who have already had a heart attack. This is likely not because of its cholesterol-lowering effects, but rather its anti-inflammatory properties in those whose arteries are already massively inflamed.

At the heart of insulin resistance is chronically elevated insulin, which results from diets high in refined carbohydrates, added sugars, and ultra-processed foods. These foods spike blood sugar levels repeatedly, forcing the body to produce more and more insulin to bring those levels down. Over time, cells become less responsive to insulin’s signal—a condition known as insulin resistance.

This matters because insulin resistance doesn’t just lead to type 2 diabetes. It is now widely recognized as a key driver of cardiovascular disease.

In contrast, low-carbohydrate and whole-food diets have been shown to improve insulin sensitivity, reduce inflammation, lower triglycerides, increase HDL, and even shift LDL particles to a larger, less harmful type. This is why many researchers argue that focusing on blood sugar and insulin control is far more effective for preventing heart disease than simply chasing cholesterol numbers.

The tragic irony is that when saturated fat was wrongly blamed for heart disease, it led to the rise of “low-fat” processed foods, often packed with sugar and refined carbs. In trying to avoid fat, we inadvertently embraced the very foods that drive insulin resistance and heart disease.

For decades, we’ve been told a simple story: cholesterol is the enemy, LDL is “bad,” saturated fat clogs your arteries, and statins are the only solution. But science no longer supports this black-and-white narrative.

What we’ve uncovered is far more nuanced—and far more empowering.

Cholesterol is not the villain it’s been made out to be. It’s essential for hormone production, brain health, and cellular repair. The real issue isn’t how much cholesterol you have, but what state it’s in. Oxidized LDL, driven by inflammation, sugar, seed oils, stress, and metabolic dysfunction, is what causes damage, not cholesterol itself.

Equally important, the cholesterol in your diet has little to no bearing on your blood cholesterol. And saturated fat? It’s not only far more complex than once believed, but also essential in its natural, whole-food form.

The true markers of heart disease risk—oxidation, chronic inflammation, insulin resistance, and metabolic health—are being overshadowed by an outdated obsession with lowering cholesterol numbers. It’s time to shift our focus.

Blindly lowering LDL with statins without addressing root causes can do more harm than good. We need to stop fighting cholesterol and start fighting the actual drivers of heart disease: poor diet, lack of nutrients, and systemic inflammation.

If we’re serious about protecting heart health, we need to stop chasing numbers—and start pursuing real health. That means whole, nutrient-dense foods, movement, quality sleep, stress reduction, and ditching the dogma of decades past.

Because the truth is that cholesterol isn’t the problem. It never was.

Cholesterol is not the villain it’s been made out to be. It’s essential for hormone production, brain health, and cellular repair. The real issue isn’t how much cholesterol you have, but what state it’s in. Oxidized LDL, driven by inflammation, sugar, seed oils, stress, and metabolic dysfunction, is what causes damage, not cholesterol itself.

In reality, dietary cholesterol has little to no impact on blood cholesterol levels for the vast majority of people. Controlled clinical studies have shown that there is not a direct correlation between cholesterol intake and blood cholesterol because the body tightly regulates cholesterol levels: when dietary intake goes up, the liver produces less cholesterol to maintain balance, and when intake goes down, the liver ramps up its production.

In the Isehara Study, based on over 21,000 adults from a city in Japan, researchers grouped people by LDL cholesterol levels—from under 80 mg/dL to over 180 mg/dL. The group with the lowest LDL (<80 mg/dL) had the highest death rates, in both men and women. While men with very high LDL (>180 mg/dL) did see slightly higher rates of heart disease, women didn’t follow the same trend. In fact, women with the highest LDL had the lowest rates of heart disease deaths.

Small changes, big impact. These ten science-backed habits boost your health, energy, and longevity.

What research says about memory, motivation, mood, and medical use—nuanced, balanced, and clear.

What science says about walking barefoot, inflammation, sleep, and stress. Simple ways to try grounding safely.

ADHD is more than distraction. Explore the latest research on causes, symptoms, and how it impacts daily life.

Overstimulation kills focus. Learn how a dopamine detox helps reset your brain, restore balance, and boost productivity.

RSD is an intense emotional sensitivity linked to ADHD. Understand its symptoms and learn ways to manage emotional triggers effectively.

You’ll Learn:

Effective Immediately: 5 Powerful Changes Now, To Improve Your Life Tomorrow.

Click the purple button and we’ll email you your free copy.