Why does the sting of a criticism invoke stronger emotion than the joy from a compliment? How does a single negative event, no matter how insignificant, have the ability to ruin an entire day?

Maintaining a positive attitude is akin to climbing a steep mountain; it can take hours of back-breaking effort to make just a few hundred meters of progress, but one small slip will send you straight back to the bottom in just a fraction of the time, often with dramatic consequences. A good climber needs to not only know how to climb, but also how to avoid falling. The same can be said for maintaining positivity.

If this sounds like you, you’re not alone. This tendency to dwell on the negative more than the positive is often referred to as the ‘negativity bias’, and it explains our tendency to dwell on and recall negative information far more readily than positive information.

This article will explain the ways in which this negativity bias affects your everyday decisions and attitudes towards life. By understanding the mechanisms behind the way our brains work, we can begin to manage it effectively for more positive results.

What is The Negativity Bias?

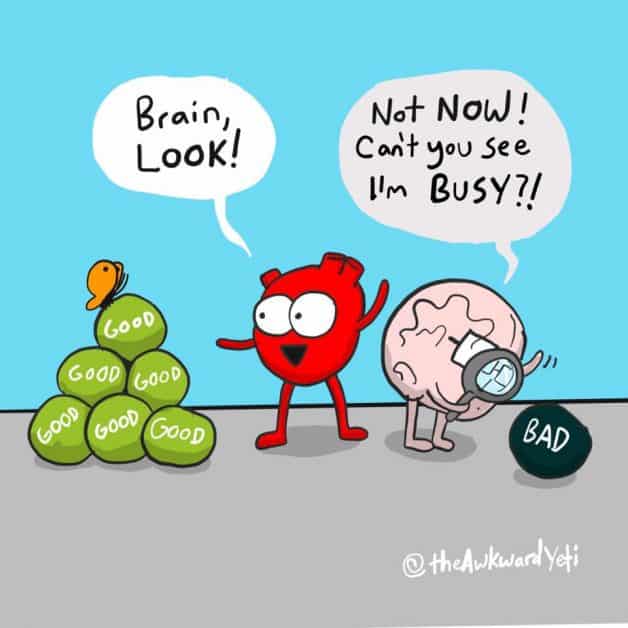

The human brain tends to recall traumatic experiences more vividly than positive ones (I’m sure you could think of three traumatic experiences far quicker than you could think of three positive ones). It also recalls insults more readily than praise, reacts more strongly to negative stimuli (think road rage) and focuses our attention more directly on negative information.

Also known as the ‘negativity effect’ or “positive-negative asymmetry’, this inherent bias describes how negative stimuli (i.e. unpleasant thoughts, emotions, or social interactions) have a greater effect on one’s psychological state than neutral or positive stimuli of equal intensity. In other words, we react much more readily to negative events and tend to dwell on them for longer.

The Effects of the Negativity Bias

The effects of this negativity bias are apparent in every facet of our daily lives. Presidential debates often focus more on the negatives of an opponent’s character as opposed to promoting the positives of their own. News outlets bombard us with negative stories which they know will hold the viewer’s attention greater than positive news.

This is an unfortunate side effect of a modern digital news industry – revenue depends on ad views, and views depend on manipulating search engine’s algorithms for clicks at any cost. As pessimistic as it sounds, negative stories sell far better than positive ones because they evoke greater emotion, and emotion sells.

I have been just as guilty of this negativity bias as anyone else. I remember my first job performance review after having moved to Canada on a journey to “find myself”.

As a junior construction project manager, I was determined to shake off the image I had always been plagued with, that I was shy, quiet and too introverted. The aim of my travels to Canada was to establish my independence and self-confidence and to become a force to be reckoned with, someone who knows what they want and will do whatever it takes to achieve it.

My first performance review started strong. Like any good evaluator, my review was delivered to me in the typical “marmalade sandwich” style – start and end with the positives (the bread) with the constructive criticisms in the middle (the marmalade).

I was told my positives – my projects came under budget and on schedule. I had a good work ethic and got along smoothly with my colleagues. It also ended on a good note. I received a sizable pay rise and a nice bonus to boot. Clearly, any review that ends with you walking out with more money than you went in with was a very good one.

But the bit in the middle, the marmalade, was what stuck with me. My manager noticed that I was quiet in meetings and perhaps didn’t seek advice or communicate with peers and colleagues as much as I should. It was simply honest feedback that I could work on to further improve my competency.

Despite all the compliments, the pay rise and the bonus, I went home that evening disheartened. I should have seen the day for what it was; an extremely positive one where I was rewarded for my hard work and was given advice on how I can further improve my performance.

Instead, I focused only on the few negatives and let it convince me that my performance was poor. Ironically, my mindset was the only real failure that day, such is the power of the negativity bias.

Many assume that this proclivity for negativity is a personality problem. But allow me to let you in on a life changing secret. The negativity bias is biological. It is inherent in you, me and every single person on this planet. It is a genetic trait etched into our DNA since time immemorial.

The takeaway from this is the reason I believe this book is so important for so many people out there who struggle to overcome their fears. Do not blame yourself for unpleasant thoughts and feelings that enter your mind. Remember, it’s not your fault if it’s not your thought.

Negativity Is Natural

There are countless self-improvement books on the market which aim to improve your positive mindset. Many, however, despite their good intentions, preach that you can largely force your way to positive thinking.

“Always think big-picture to eliminate negative thinking for good!” and “You are what you think you are” are just two recent examples I have read that boil down to little more than wishful thinking. Unfortunately, there is no simple trick or technique that can eliminate negative thinking. If it were that simple there would be very few stressed or unhappy people roaming the Earth.

The Science Behind the Negativity Bias

The negativity bias is so dominant for a very good reason. In fact, mankind has relied on this trait to keep us safe for thousands of years and it has allowed us to emerge as the dominant species.

The bias is likely the result of thousands of years of evolution, where paying greater attention to negative (and thus potentially dangerous) threats was literally a matter of life and death. Those who were more instinctively attuned to imminent danger were more likely to avoid it.

It is far less consequential to overestimate a threat than to underestimate it (overestimate it and you may miss out on a meal. Underestimate it and you may end up being the meal!). It is survival of the fittest at its finest.

Although just a theory, science has evidence to support it. Neuroscientific experiments, where the brain’s response to negative stimuli was measured through event-related brain potentials (ERPs), showed that the brain’s response to specific negative stimuli elicited a larger neural response than that derived from positive stimuli.

This indicates that the brain is hardwired to be stimulated by negative emotions to a greater degree than positive ones. To fight this would be to fight every natural instinct inherent in us.

In a similar study conducted by psychologist John Cacioppo, participants were shown pictures of either positive, negative, or neutral images.

The researchers then observed electrical activity in the brain in a similar manner. Negative images elicited a much stronger response in the cerebral cortex than did positive or neutral ones, further inferring the brain’s tendency to react more readily to negative information.

Further anecdotal experiments have also revealed this biological law. A hypothetical medical procedure was presented in two opposing manners to willing participants.

The first identified the medical procedure as having a 70 percent chance of success, of which the majority concluded that it was a good procedure, whilst the second group had the procedure presented to them as a 30 percent chance of failure, of which the majority identified as risky. The exact same experiment presented from two different opposing manners significantly changed the participants’ view of it.

The second part of this experiment was even more interesting. When the group who were previously happy with the 70 percent chance of success were then explicitly told of the 30 percent chance of failure, the majority changed their view of the procedure and thought it risky (as the group who originally viewed it as negative did).

Conversely, when the group who were originally told of the 30 percent chance of failure were then told it was a 70 percent chance of success, they did not change their minds. The negative viewpoint had already stuck with this group and a positive redirection was not enough to change it.

The key finding here is that it is easy to switch from a positive to a negative mindset and more difficult and slower to shift away from a negative one. Although simply anecdotal, these findings reinforce that which has been found through neuroscientific research. The brain is hardwired to fixate more on the negative, and it is more difficult to switch a viewpoint from positive to negative than it is the other way.

The swings and moods of the economy is also a telltale sign of this bias in action. When the economy suffered from the great depression, public confidence in the economy dropped exactly in line with it.

Yet when the economy started to recover, public confidence also increased alongside its rise as it did with the drop, but there was a significant and noticeable lag, indicating a prolonged feeling of negativity among the public despite the economy’s improvement.

Conclusion

Mindfulness of this mechanism is the single most powerful tool in managing negativity. When we understand that being scared, worried or anxious is simply our primitive subconscious mind (of which we have no control over) trying its best to protect us, we arm ourselves with the valuable knowledge that we did not choose these feelings, and therefore cannot be judged by them.

At the very least, we can take comfort in this and somewhat reduce the associated stresses. With time and experience, we can learn to communicate with the subconscious mind and limit its effects altogether.

FAQs

Why do negative events feel stronger than positive ones?

Negative events trigger a stronger neural response than positive ones. The brain evolved to prioritize threats for survival, making bad experiences feel more powerful and memorable.

What causes the negativity bias in everyday life?

Our subconscious reacts faster than our logical mind, pushing us to notice danger first. News, arguments, criticism, and uncertainty all amplify this built-in survival mechanism.

Can you reduce the effects of the negativity bias?

Yes. Mindfulness, reframing, and conscious awareness help separate emotional reactions from reality, making it easier to stay calm and keep negative thoughts in perspective.